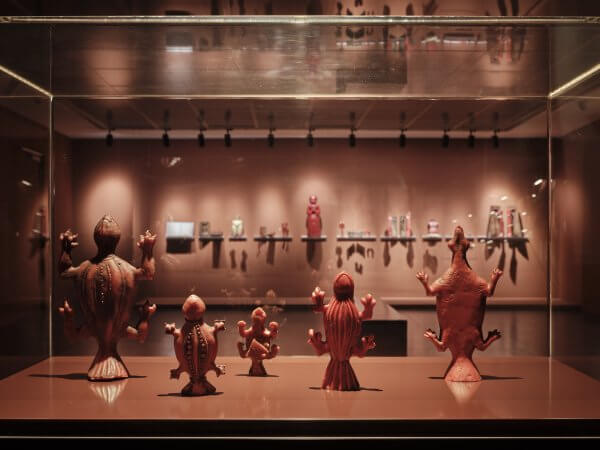

Anatomical votives from the Hans and Benedikt Hipp Collection

21 wax casts. Mid to late 20th c.

Six Wooden moulds, 1730–1800

Presented in the following order: wooden mould with torso votive; torso and back votives and lung votive with heart; wooden mould with leg votives; female votive figure; lung votive with throat; eye votive with wooden mould and er votives; arm votives with wooden mould; torso votives; tooth and knife votive; leg votives with wooden mould; toad votives (uteruses).

Photographic reproduction of a miracle book from Scheyern Abbey

Photo: Anton Brandl

Dimensions variable

Courtesy Hans and Benedikt Hipp Collection

Votives are offerings that people present to higher powers in times of need. They are prayers made tangible—petitions for healing, for protection in moments of suffering or thanks for miraculous rescue and aid. For thousands of years, this form of invoking divine power and intercession has remained almost unchanged. Even the forms of the votive gifts have changed little: they represent diseased body parts, organs or figurative situations. Votives may be paintings or three-dimensional objects. The latter are made of clay, wax, wood or metal, produced either as unique pieces or as serial objects. To this day, pilgrimage sites, sanctuaries and churches are adorned with them. And bound to each individual votive is the life story of a person, whose plea is told through the gift in the form of the votive.

The Lebzelterei (a traditional workshop producing gingerbread and devotional wax objects) on the main square in Pfaffenhofen has existed since the early 17th century. Since 1897 it has been run by the Hipp family—today in its fourth generation. Hans Hipp is one of the last wax modellers and gingerbread makers (Lebzelter) still active in Germany. He has conducted in-depth research into the history of the craft, of customs and of votives, written books on the subject and established a Lebzelter and Wax Museum for his extensive collection. Thanks to his generous loans, the exhibition Anatomy of Fragility offers unique insights into the collection—and thus into the history of human experience of physical vulnerability.

In southern Germany, votive offerings were made primarily of wax from the Baroque period onwards. In Christianity, beeswax was regarded as a sacred material: pure, incorruptible and closely linked with the symbolism of the bee, which stood for purity and innocence and embodied devout Christians. At the same time, beeswax possesses a special materiality: soft, malleable and adaptable, yet also fragile. These qualities are directly connected to the fleshly nature and vulnerability of the human body, making wax the ideal material for votive offerings.

Their production was the responsibility of the Lebzelter—a guild that, according to its statutes, was at that time the only one permitted to work with bee products. The profession of the Lebzelter included not only the baking of gingerbread and honey cakes, but also candle making and the casting of votive offerings. The artful carving of three-dimensional wooden moulds, used both for pastries and for votive objects, was then an important part of the Lebzelter’s training. Moulds are negative forms into which wax or dough is pressed to produce a raised image.

From yellow, bleached or red-dyed wax, the Lebzelter cast limbs, organs or symbolic forms. Anatomical accuracy played only a minor role, yet the shapes were familiar to people—like a visual vocabulary in times when few could write.

For internal organs, slaughtered animals often served as models, while other anatomical forms were deliberately simplified or represented symbolically. One example is a votive in the form of a toad, intended to illustrate the uterus. Popular belief at the time held that a toad sat in a woman’s belly, biting her and thereby causing menstrual pain and bleeding. This notion goes back to ancient ideas. In Greek medicine, the uterus was sometimes described as a freely moving, independent being that wandered through the body. At the same time, the toad has been regarded in many cultures as a symbol of fertility.

Most of the votive figures in the Hipp Collection were destined for the pilgrimage church of Niederscheyern (Unsere Liebe Frau, U.L.Fr.), only two kilometres away. They were laid down together with monetary offerings (the so-called Opfer in Stock) and a vow to have a mass celebrated. Ten so-called miracle books (Mirakelbücher) have been preserved in the archives of the Benedictine monastery of Scheyern, and one of them is displayed in the exhibition as a photographic reproduction. Between the late 17th century and 1803, more than 20,000 ‘vows’ were recorded. Clergymen collected oral reports from the faithful about their miraculous healings and set them down in writing. Through these records, it is possible to trace the connections between the votive offerings of the Hipp Collection and the corresponding illnesses, as well as the stories and destinies of those affected.

These records are like windows into the everyday lives of ordinary people: they tell of their faith, their worries and hopes, their ways of dealing with illness and recovery. They document a world view in which medical help often failed and healing was sought through faith. At the same time, they serve as a medical-historical compendium, providing insight into anatomical knowledge, concepts of disease, healing practices and body images of past centuries.

In the Middle Ages, medical care in rural areas was provided mainly by monasteries. Nuns and monk-physicians maintained pharmacies and herb gardens. With the Renaissance, monastic medicine lost its importance. Secular doctors—the so-called medici—were now trained at newly founded universities. At that time, however, they treated only wealthy patients, and medical care for ‘ordinary people’ was left to lay healers known as Bader. Their knowledge was not based on academic training, but on practical craft. After just two to four years of apprenticeship, one could practise this profession, while further experience had to be gained through success or failure with patients. In addition to local Bader, there were also itinerant healers who offered their services in marketplaces. They were often accompanied by fire breathers and sword swallowers who drew attention to them, while drummers, pipers and criers attempted to drown out the cries of pain from their patients.

With secularisation in 1803, the continuation of the miracle books was prohibited by the state, as they were regarded as a promotion of ‘error and superstition’.

Behind every piece of wax, however small, lies a personal destiny. Even if many figures were cast from the same mould and appear identical in form, each carries within it an individual story, a wish or an urgent hope. They are an expression of faith and trust, and at the same time, of having no other recourse to heal their pain.

Miracle books:

The miracle books of Scheyern reveal that petitioners often turned to God for help only after several unsuccessful treatments by the Bader. They purchased a votive offering from a nearby Lebzelter, endowed it with their plea, and laid it down in a pilgrimage church together with a vow to have a mass celebrated and a monetary donation (Opfer in Stock).

Helena Pfabin from Schacha had a thorn in her foot for three and a half years and could no longer walk. She also sought help from various Bader, but they were unable to remove the thorn. So she made a vow to the Holy Cross, offering a wax foot and an Opfer in Stock. Thereupon the thorn sprang out of the afflicted foot by itself, to the greatest astonishment of the suffering woman.

Book of Good Deeds, Scheyern Abbey, 1743, No. 5

Supplicant (Votive Female Figure):

Some believers had their portrait or even their entire body modelled or cast in wax. The closer the figure matched the supplicant in size and weight, the greater the symbolic—and at the same time the material—value of the votive offering. It represented the dedication of the whole person, often in the context of a comprehensive plea for healing or protection.

Anna Gräslin of Scheyern lay gravely ill, so much so that no one believed she could recover. In this most desperate danger she made a vow here, with a wax effigy and an Opfer in Stock. Thereupon her condition gradually improved, and in fact she recovered.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 5, 1749, No. 81

Toad:

The votive in the form of a toad symbolises the uterus. In popular belief it was thought that a toad dwelt in a woman’s womb, causing pain and bleeding. By offering such a gift, women sought healing from abdominal ailments or relief from unfulfilled desire for children.

Walburga Heiflin of Unterschönbach had suffered for fourteen days from severe pains in her womb, as if bitten. She therefore made a vow with a waxen womb and carried it on her bare knees around the altar. After this vow, the illness ceased at once, without doubt through the intercession of the helper in need, St Leonard.

Miracle Book of Inchenhofen, 1592

Eyes:

Eye votives were offered in cases of injuries and diseases of the eyes, often also out of fear of blindness.

Walburg Kneißlin of Reisgang suffered from a dangerous condition of the eyes and feared she might go blind. Yet as soon as she made a vow here in offering a wax eyeball, she felt relief and regained her sight.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 4, 1726, No. 109

Teeth:

Tooth votives and dentures were offered in cases of toothache and oral diseases. They were often intended to bring relief or to protect against further suffering.

Maria Renkhl suffered from severe toothache for a full 24 days. She made a vow here with a holy rosary and a wax set of teeth, whereupon the pain soon subsided.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 5, 1747, No. 28

Ears:

Ear votives were offered in cases of earache, hearing loss or deafness. They were intended to bring healing and the return of hearing.

Rosina Kiefflin, unmarried, from Pfaffenhofen, suffered from a severe defect of hearing, so that for five weeks she could hear neither speech nor bells. She sought help from Our Lady here, vowing to pray three rosaries and to make an offering. She immediately perceived an improvement.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 2, 1706, No. 101

Arms, Legs and Hands:

Moulds for casting arms, hands and legs belonged to the standard repertoire of every Lebzelter. Hardly any pilgrimage church could do without these votive offerings: they were given in cases of injury, paralysis or serious illness and were often laid down in large numbers together with crutches and bandages—as petitions for healing or as thanks for recovery.

A child from Pfaffenhofen had such a severe condition of the finger that a Bader treated it for three-quarters of a year, but to no avail. It was even thought that the child’s finger would have to be amputated. In this distress the parents finally placed their only hope, next to God, in the image of grace here, and vowed the child with a holy mass and an Opfer in Stock. Immediately all danger disappeared, and the finger was healed.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 2, 1705, No. 53

Wolfgang Krebs, a soldier, was severely wounded in the right hand and lay bleeding for four hours, unable to help himself, and with no one else coming to his aid. As a result, his injured hand became completely paralysed, so much so that for five months he could not move it or hold the slightest thing. But when, after these five months, he passed by this house of God as a discharged soldier and heard many people speak of this image of grace, he made a vow with a wax hand and a Kreuzer (a small coin) in the Opfer in Stock. Thereupon he was immediately able to move his hand again and use it at will.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 2, 1702, No. 13

Torsos:

A wax torso was usually offered in cases of pain in the chest or abdominal area, or in diseases of the internal organs. Since self-diagnosis was often difficult with the wide variety of pains in the upper body and abdomen, it was easier for the sick to symbolically locate all their complaints in this region and to express them in the form of a wax torso.

A certain person was in great fear because of a swelling on the chest, worrying it might turn to cancer. To avert such misfortune, they vowed a holy mass and a wax offering, and were thereby freed from further harm with great consolation.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 4, 1726, No. 223

Knives, stabbing pains:

All stabbing pains, especially those in the chest and abdominal area, were indicated by a wax stabbing knife. Pains of the heart, lungs or side were among the most frequent reasons for such votive offerings.

Maria Winderin of Eidenbach was suddenly seized at night by a painful stabbing in the heart, so that she could neither move nor bend. In this pain she made a vow here with a wax stabbing knife, a Saturday devotion, and an Opfer in Stock. Upon this prayer the stabbing pain in her side ceased immediately.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 5, 1748, No. 32

Lungs:

Lung votives were offered for diseases of the respiratory tract and neighbouring organs, often also for tuberculosis, which at that time was called ‘consumption’ or ‘lung disease’.

Catharina Kneißlin of Pfaffenhofen was so severely afflicted with coughing that she spat blood. But as soon as her mother made a vow that the daughter should come here on three consecutive Saturdays, and also offer a wax figure, she immediately began to recover.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 2, 1703, No. 21

Throat:

Votives in the form of a throat or gullet were offered for illnesses in the throat area, such as inflammations, ulcers or breathing difficulties.

Magdalena Moserin of Säzlhof suffered from a dangerous condition of the throat. There was no doctor experienced enough to help her. She declared that Our Lady of Niederscheyern alone was her best helper and physician.

Miracle Book of the Niederscheyern Pilgrimage Site, Vol. 4, 1725, No. 83