Anatomical Wax Collection “Luigi Cattaneo” and Museum of Palazzo Poggi, University of Bologna

For the exhibition Anatomy of Fragility, selected works from the Museum of Palazzo Poggi and the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection at the University of Bologna have been brought together. Both collections hold several thousand objects, including one of the most significant holdings of anatomical wax models in Europe. The exhibition presents exemplary pieces from different periods and by various artists. From the 18th century onwards, the University of Bologna employed art and wax as a means of vividly exploring the human body, thereby becoming a pioneer in medicine.

Founded in 1088, the Alma Mater Studiorum is the oldest University on the European continent. It dates back to 1088, and among its many distinguished alumni are Petrarch, Dante Alighieri and Copernicus, as well as Pier Paolo Pasolini and Umberto Eco. The exemplary role of the University of Bologna contributed to the founding of numerous other universities across Europe and to the spread of the modern university model. From early on, anatomical research in Bologna was closely linked with artistic representation. Support from the Catholic Church played a decisive role in this process, granting artists an official function in the depiction and imparting of anatomical knowledge.

The science of anatomy began in ancient Alexandria in the 3rd century BC with the first scientific dissections of the human body, although knowledge of the human body was for a long time acquired mainly through the dissection of animals. For centuries, from antiquity to the Renaissance, the view into the interior of the human body remained strictly regulated. Religious, moral and social prescriptions determined what was permitted, and anatomical dissections were often allowed only under exceptional circumstances. At universities such as Bologna, the teaching of the body was initially based on ancient writings, without verifying this knowledge on the human body itself.

In the Renaissance, these prohibitions began to loosen. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo sought to depict the human body with the greatest possible precision. Their work contributed to the Catholic Church’s recognition of the scientific value of anatomy. Anatomical studies were no longer regarded as a contradiction to faith, but as a complementary path towards understanding the human body as the pinnacle of God’s perfection.

As early as the late 16th century, the first anatomical theatre was established in Bologna. Here, dissections of corpses could be carried out before students and interested spectators. At the same time, the first collections of prepared body parts and organs were created, yet the use of real corpses was limited: they decayed quickly, were available only in small numbers and for hygienic reasons could not be employed indefinitely for teaching and research.

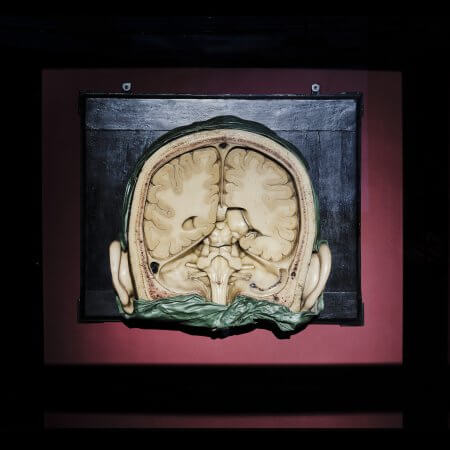

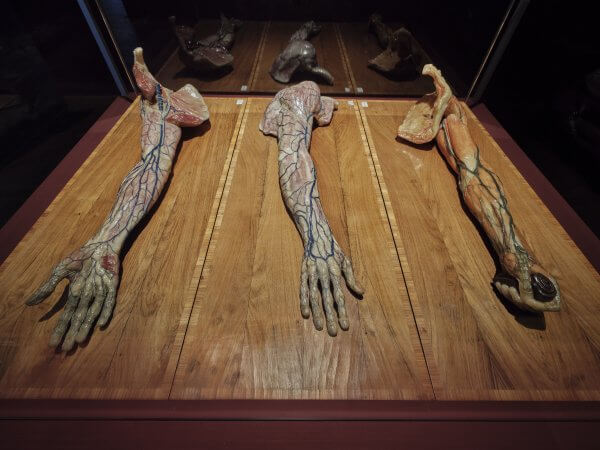

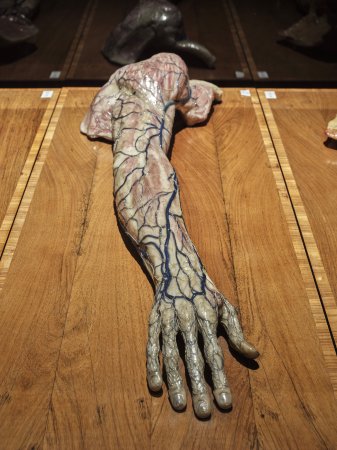

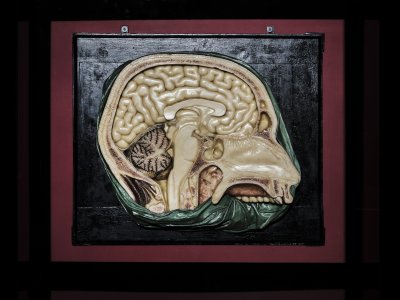

So to give students and researchers a precise view of the human body despite these limitations, art and science entered into close collaboration with a particularly pragmatic solution: wax. Malleable, durable and capable of being coloured with realistic tones, this material made it possible to create lasting and lifelike reproductions of the human body. No other medium appears so true to life. The wax figures from Bologna reveal muscles, organs and nerve pathways—a glimpse beneath the skin. They allowed students and researchers to study the body in detail without having to rely on fragile corpses.

The history of anatomical wax figures for didactic purposes began in Bologna. In 1742, Pope Benedict XIV, the ‘Enlightenment Pope’, supported the establishment of the Anatomical Cabinet in the Palazzo Poggi. There, the Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture were brought together under one roof. Artists and scientists worked side by side to reproduce the human body in wax with lifelike accuracy. Commissioned by the Pope, the artist Ercole Lelli created the first life-sized wax figures, which revealed muscles, organs and the skeleton layer by layer. This marked the beginning of modern anatomical wax modelling in Bologna—a tradition that lasted for more than 150 years.

The first wax models were created for teaching and training purposes. Later, doctors also used them for research and for the diagnosis of pathological conditions. These works eventually gave rise to collections that systematically documented human anatomy.

Today, visitors to the University of Bologna can discover two important collections. Firstly, that of the Museum of Palazzo Poggi, which preserves the reconstructed collections and laboratories—such as the Anatomical Cabinet—of the former Istituto delle Scienze e delle Arti. And it illustrates how science, art and medical history converged here. Secondly, this collection is complemented by the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection, which demonstrates both normal and pathological anatomy. Wax models, bones and dry specimens form an illustrative didactic ensemble, showing how the University of Bologna became a European centre of excellence in medical research between the 18th and 19th centuries.