Moulage Collection of the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology; University Hospital, Goethe University Frankfurt

21 Moulages, 19th-20th c.

Painted wax, fabric, wood

Dimensions variable

Courtesy Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology; University Hospital, Goethe University Frankfurt

Moulages are three-dimensional, lifelike reproductions of body parts made from wax. They depict diseases and injuries and were created for use in medical training.

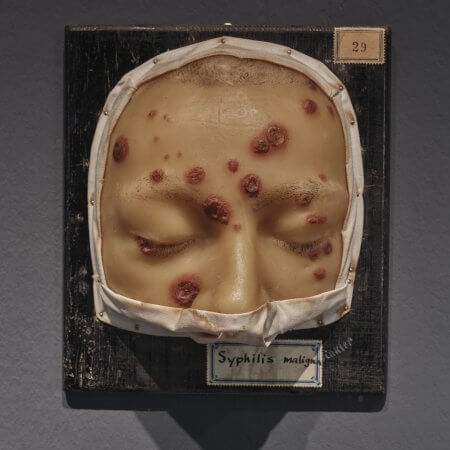

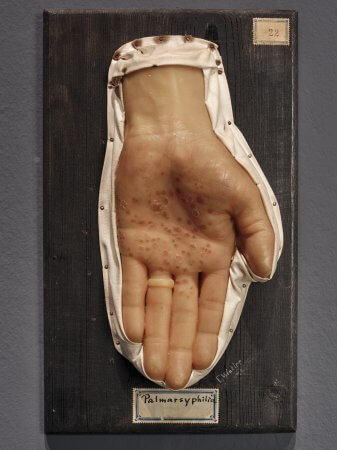

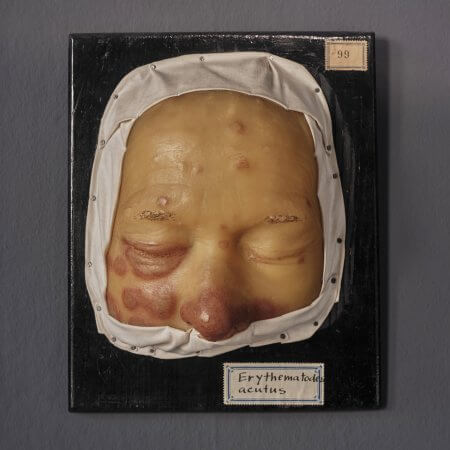

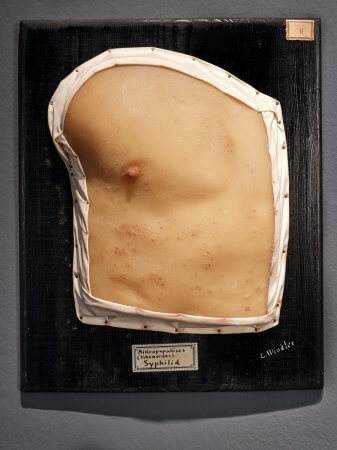

For the exhibition Anatomy of Fragility, the Frankfurter Kunstverein collaborated with the Goethe University Frankfurt to present a selection of objects from the collection of the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology at the University Hospital Frankfurt to an interested public. They are still used today as teaching aids in medical education and illustrate the manifestations of pathologies such as cutaneous tuberculosis, syphilis, cancer, shingles, psoriasis and fungal infections. Some of these conditions are now curable, others remain dangerous.

The Frankfurt moulage collection was established in 1894, at the same time as the founding of the Department of Dermatology. Today the collection comprises more than 300 moulages, the oldest dating from 1904—the year to which the only dated specimen also belongs. The wax models belong to a time when sight was one of the most important tools of diagnosis. Physicians observed the signs of disease with precision, described them and compared them with other cases. It was during this period that the skin was first recognised as an organ in its own right. From the late 19th to the early 20th century, these meticulously detailed models were the most important visual media of dermatology.

The term moulage derives from the French mouler—to mould, to cast. It refers to a technical process that has long been a standard method in sculpture. To produce moulages, diseased areas of patients’ skin were moulded directly in plaster, creating a negative form. Liquid wax mixtures were then poured into the negative, and the positive cast was tinted with pigments to achieve the desired base tone. Colouring took place in the presence of the patients, with skin tones and pathological features reproduced as faithfully as possible. Scars, crusts or blisters were additionally modelled from wax, resin or other materials. Details such as eyes, hair or disease-specific alterations were sculpted or applied.

The moulages bear two paper labels on their front: one with a handwritten diagnosis, the other with a number that presumably belonged to a now lost system of order. Inscriptions or signatures are inconsistent. On some of the Frankfurt moulages the artists’ signatures can still be seen. Ernst Winkler (1877–1907) was likely the first wax modeller permanently employed at the clinic. After him, a woman took over the position—yet in the records her name appears only as ‘1 Moulageuse’.

Among the signatures in the Frankfurt collection, the name of the internationally renowned Jules Baretta stands out. Baretta (1834–1923) was a moulageur at the Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris. Knowledge of the techniques, materials and artistic procedures of moulage-making was for a long time passed on only within a small circle. Baretta influenced the development of dermatology and the art of moulage throughout Europe. At the First International Congress of Dermatology, held in Paris in 1889, Baretta’s moulages were met with great admiration. This led to the rapid spread of the technique to other clinics across Europe. On view in the exhibition is model no. 76 by Jules Baretta, Tinea faciei, a fungal disease of the skin of the face.

The idea of documenting diseases with lifelike wax models first emerged in the 17th century in Bologna and Florence. Felice Fontana, then director of the natural history museum La Specola in Florence, was convinced that pathological anatomy in the form of wax models could help to better understand the causes of disease. His proposal to establish a dedicated collection as a museum, however, was rejected by the authorities. Such models were deemed appropriate only in hospitals, not in museums, which were considered places for the edifying and the beautiful. Thus the first collections of pathological anatomy were created in hospitals, where they were initially used for research and cataloguing, and later also for the training of physicians.

With the introduction of colour photography and the possibility of producing and disseminating images more quickly in medical documentation, moulages lost their importance from the mid-20th century onwards. Having fallen into obscurity, the collection of the University Hospital in Frankfurt was only rediscovered in 2012. Since then, on the initiative of Prof. Dr Falk Ochsendorf and under the current head of the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Prof. Dr. Bastian Schilling, it has once again been used for teaching purposes.

Studies have shown that students who work with dermatological wax models are more likely to develop empathy for patients than those who learn only from photographic images and medical texts. The lifelike, corporeal form can create a sensory experience that may foster the capacity for compassion with another human being who is ill.

Moulage 0002, labelled P.A. Lippe, shows a so-called primary lesion of syphilis on the lip. Since the early 2000s, syphilis—after having almost disappeared in Germany—has been on the rise again. The cast was taken directly from an affected person, and on close inspection one can discern the imprints of the fingers that held the lip in place during the moulding process.

Moulage 22, labelled Palmarsyphilid, shows a syphilitic rash on the palm of the hand. In addition to the lifelike depiction of the skin lesion, the detail of a wedding ring stands out. For a fleeting moment, the medical object becomes a personal testimony, a trace of the life and story of the person whose body was cast. Moulages 29 and 6 show further manifestations of the infection.

Moulages are fascinating phenomena. They are meticulously crafted three-dimensional representations of bodies, whose makers often remained anonymous and did not associate their skill with the idea of artistic creation. And yet the objects had an impact on society. Once they eventually became part of public museum collections, they served as instruments of warning and deterrence. Numerous diseases—particularly sexually transmitted ones—were incurable. Those who contracted them were additionally subject to social stigmatisation.

Syphilis has had a profound influence on both art and literature. Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut Syphilitic Man depicts the disease as divine punishment. The painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, himself afflicted with syphilis, portrayed figures from the Parisian nightlife of the Moulin Rouge, where the disease was widespread. The writer Guy de Maupassant, also affected, described syphilis as ‘the revenge of prostitutes’. Charles Baudelaire, Heinrich Heine, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Oscar Wilde, Ludwig van Beethoven and Robert Schumann—whose final years were marked by delusions as a late consequence of syphilis—were likewise afflicted. The disease only became curable around 1945, with the discovery of penicillin.

Other moulages show symptoms of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a late manifestation of Lyme disease that was only identified in the 20th century. Fungal infections of the face were historically not regarded as pathology but, in superstition, as divine punishment. The same applied to pigment disorders following inflammation or to internal diseases that manifested on the skin—such as the leukaemic infiltrates of cancer, made visible on the surface. Lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease in which the immune system turns against the body itself. Boeck’s sarcoid, which affects both the skin and the internal organs.

Other moulages speak of the impact of the environment and industrialisation on the body: inflammations of the hair follicles or eczemas that break out and worsen as a result of work, climate or living conditions. For example, chloracne, caused by industrial chemicals such as dioxins.

Anyone viewing a moulage today sees not only a teaching model of a disease with its visible, bodily effects, but also a preserved exact likeness of a real, individual person—unlike the anatomical wax models of the Italian tradition, which depicted idealised and anonymous bodies. They are thus the image of a bodily fragment that bears the traces of a real human being and their unique history of suffering.

The striking impact of moulages lies in their lifelike quality and their material. Wax can be shaped, coloured and used to reproduce the living body with deceptive realism. At the same time, it carries a symbolic dimension. The art historian Georges Didi-Huberman describes beeswax as an ‘extremely sensitive, indeed unstable natural material’ that, almost of its own accord, conveys the fragility and transience of the body. Its plasticity, instability and sensitivity to warmth allow it to ‘become flesh’ and to impart a sense of living corporeality.

This fragility is also reflected in the objects on display. Many moulages, which lay unnoticed in a cellar for decades, now bear cracks and traces of time—caused either by the ageing of the material or by their earlier use in teaching. They speak not only of the fragility of the bodies depicted, but also of the inherent vulnerability of the medium of wax itself—a material that can also be found in other works and objects in the exhibition Anatomy of Fragility.

The following moulages are shown in the exhibition: Lupus, autoimmune disease with skin changes (69 Erythematodes acutus disseminatus); Fungal infection (76 Tinea faciei); Late manifestation of Lyme disease on the skin (157 Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans Herxheimer); First visible signs of syphilis (002 P.A. (primary lesion) lip); Lupus with exacerbation (Erythematodes c. exacerbatione acuta); Warty tuberculosis (56 Tuberculosis cutis verrucosa (hand)); Toxic acne caused by environmental toxins (115 Chloracne); Chronic progressive inflammation of the skin (159 Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans Herxheimer); Lupus, inflammatory autoimmune disease (99 Erythematodes acutus); Skin lightening after inflammation (119a Postinflammatory hypopigmentation); White spots in the neck area (20 Leukoderma nuchae); Spotty leprosy with sensory disturbance (132 Lepra maculo-anaesthetica); Skin changes in leukemia (197 Leukemic specific infiltrates); Signs of syphilis in an advanced stage (6 Micropapular (lichenous) syphilid); Malignant course of secondary syphilis (29 Syphilis maligna); Syphilitic rash on the palms (22 Palmar syphilid); Inflammatory change of the sebaceous glands (181 Seborrheic eczema Unna’s dermatosis); Skin lightening after inflammation (118 Vitiligo); Chronic inflammatory disease with nodule formation (49 Boeck’s sarcoid (Lupus pernio)); Inflammatory skin disease with keratinization of the hair follicles (102 Dermatitis follicularis hyperkeratotica); Psoriasis (22a Psoriasis (back of the hand)).