The anatomical Venus by Clemente Michelangelo Susini and the workshop for wax sculpture in Florence

Venerina (Reclining female figure with detachable anatomical parts), 18th c. (ca. 1782)

Anatomical model in painted wax, hair, wood, fabric and pearls

Body 138 x 57 x 26 cm; with frame 165,5 x 75 x 47 cm

Courtesy Alma Mater Studiorum – University of Bologna | University Museum Network | Museum of Palazzo Poggi

This sculpture, an anatomical figure created in 1782, belongs to the spectacular collection of the Museum of Palazzo Poggi at the University of Bologna. It is a wax model of a female figure, shown lying on a bed, her head tilted back, her body slightly twisted and wearing a pearl necklace around her neck. Long real hair frames her face and covers her pubic area. From the collarbones to the pubis, her body is opened, the internal organs exposed. One sees the heart within the chest, the liver, kidneys, bones, nerves and veins, as well as the uterus containing an unborn child. The abdominal wall, trunk muscles, intestines and further organs are arranged around the body. And the figure lies open as if on a medical dissection table, yet staged as a sleeping beauty in the moment between life and death.

The so-called Venerina (little Venus) was modelled on the body of a young woman who had recently died. Unlike many other wax figures, which were composed from parts of several corpses, its interior derives from a single, intact body. Today it can be recognised that the woman died of a congenital heart condition. She was five months pregnant. The enlarged heart, the dilated blood vessels and the small foetus reveal the cause of her early death.

Only eighteen such life-sized anatomical female figures exist worldwide. They are known as ‘anatomical Venuses’ and trace their origin to a first figure created by Clemente Michelangelo Susini (1754–1814), who, on commission from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, fashioned it out of beeswax for the Florentine court. Each is unique in its composition. Reproduced with the utmost precision, the figures reveal the inner organs, whose functions were often still unknown at the time.

The Florentine wax workshop in which Clemente Susini worked had its origins in that of the University of Bologna. While in Bologna lifelike wax models were produced primarily for purposes of research and teaching, the figures in Florence were intended as demonstration models for a broader public. As the workshop’s leading master and artist, Susini worked closely with anatomists, and for the newly founded natural history museum La Specola, they created the anatomical models: they would dissect the bodies and prepare the specimens for the workshop. Susini carved structures from blocks of wax, modelled and heated wax masses, or cast organs directly from the original specimens. In addition, he employed plaster negative moulds to permanently capture the form of the organs. These moulds could be reused, and this technique made rapid and precise reproduction possible upon first use.

Susini’s distinctive hallmark and artistic innovation was a novel synthesis of scientific precision and artistic interpretation. He was shaped by the artistic currents of his time: the drama of the Baroque and the Neoclassical ideal of the human body. This ideal was informed by notions of harmony, balanced proportions and timeless beauty, as known from ancient art.

The Florentine wax workshop still enjoys an international reputation today. At the time, it produced a great number of wax models, which were sent to museums and universities across Europe. The figures were always the result of collaboration between craftsmen from the arts and scholars from medicine and anatomy.

The Florentine Specola was the first museum of its kind in the Western world. Even then, it was open to all, yet with strictly segregated visiting hours according to social class: on the one hand, for ‘neatly dressed’ visitors from the lower classes, and on the other, for the ‘educated’ members of the upper classes. The collection comprised nineteen complete male and female anatomical figures—only a few of them constructed to be dismantled in layers—and more than 1,400 wax models of individual organs and body parts, as well as specimens of comparative anatomy and zoological objects.

The founding of the museum in 1775 coincided with a time of upheaval, as the rule of the Medici in Florence came to an end. The new rulers from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine promoted science and education with the aim of systematically recording knowledge of nature and applying it for the benefit of society. This Enlightenment climate also shaped Clemente Susini’s work.

For us today, the anatomical Venus is more than a mere teaching aid. She makes clear that science always reflects the intellectual, cultural, aesthetic and emotional conceptions of its time and conveys its cultural context. In her, it becomes evident that medical knowledge is never purely objective, but is instead permeated by artistic and aesthetic principles.

The anatomical Venus presents a notion of femininity inseparably linked with motherhood. This is evident both in her depiction as a pregnant woman and in the medical focus on the female reproductive organ—as if the primary function of the female body and the role of women in society were reduced to reproduction. Her passive, devoted pose renders her at once an object of scientific scrutiny and of erotic desire. Today, this image can also be read as an expression of the male gaze.

The seductive posture of the anatomical Venus arises from an artistic decision. Anatomy is conveyed not only by displaying structures, but by placing the body’s capacity to feel, to desire and to suffer at the centre. The pose of the anatomical Venus illustrates the notion of fragility and the suffering inherent in corporeal existence.

This reflects a central paradigm shift of the 18th century: previously, conceptions of the body had been shaped by ecclesiastical and religious ideas. With the Enlightenment, the body began to be studied empirically, and it was recognised that it responds to stimuli through a complex system from which sensations arise.

Testa, tronco e arto destro con dimostrazione della circolazione sanguigna e linfatica (Head, torso and right arm with a demonstration of the blood and lymphatic circulation), 1810

Anatomical model in painted wax using mixed technique

115 x 70 x 26 cm

Apparato visivo con dimostrazione delle sue varie parti (Visual apparatus with a demonstration of its various parts), 18th c. (1790)

Anatomical model in painted wax, wood, fabric

51,5 x 38 x 11,5 cm

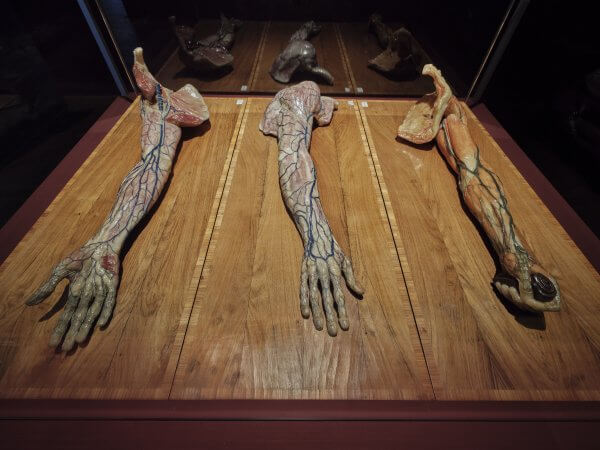

Vene e nervi superficiali della superficie palmare dell’arto superiore destro (Superficial veins and nerves of the palmar surface of the right upper limb)

Vene e nervi superficiali della superficie dorsale dell’arto superiore destro (Superficial veins and nerves of the dorsal surface of the right upper limb)

Vene superficiali dell’arto superiore preparato dopo l’asportazione della fascia superficiale (Superficial veins of the upper limb, prepared after removal of the superficial fascia)

18th–19th c.

Anatomical wax models, painted, mixed media, wood

95 x 39,5 x 24,5 cm; 95 x 39,5 x 24,5 cm; 95 x 39,5 x 22,5 cm

Courtesy Alma Mater Studiorum – University of Bologna | University Museum Network | “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection

Alongside the Venerina, the exhibition Anatomy of Fragility also presents later works by Clemente Susini from the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection in Bologna. Produced in the early 19th century as teaching material for medical training, they stand in sharp contrast to the gracefully staged Venerina: here, sober accuracy and scientific precision prevail. This shift in style reflects a change in patronage—from the museum-going public to the university of Bologna.

One model depicts the upper body of a woman without the left arm, and on the neck, head and right arm, the skin has been removed to reveal the arteries, veins and lymphatic system. The lymph nodes in the armpit, the side of the neck and the nape of the neck are especially prominent. The front wall of the chest and abdomen is also open, exposing the dense vascular and lymphatic structures near the inferior vena cava and the aorta. And the small intestine has been removed in order to uncover the vessels lying behind it.

That the lymphatic system is represented with such precision points to Susini’s close collaboration with the anatomist Paolo Mascagni. Together, they created models that gave visual form to Mascagni’s groundbreaking discoveries. Susini’s work was based on meticulous studies: around 300 dissections and the use of mercury to fill the vessels. Remarkably, he even depicted lymphatic vessels in the brain—a structure only confirmed in 2014 through modern imaging techniques. In contrast to the Bolognese wax models, which are built around real human bones, this work is made entirely of wax, with metal supports providing stability—typical of Susini’s Florentine production.

Another wax model is devoted to the human visual apparatus in all its parts. From the opened skull to the layers of the eyelid and the eyeball itself, the structures are laid bare. Visitors can explore the outer form of the eye, the muscles, the lens and the interior of the eyeball in individually crafted, carefully executed modules. Every detail is precisely modelled, allowing the complexity of vision to be experienced in a vivid and tangible way.

Three further models depict human arms in different layers. One arm, stripped of skin and superficial fascia, reveals the superficial veins; another shows the palm of a right arm with veins and nerves; the third displays the back of the hand with the same structures. Susini reproduced even the finest courses of vessels and nerves with lifelike accuracy.

However, many models were produced after his original prototypes by pupils and collaborators, making it difficult to distinguish originals from workshop pieces. These three arms may have been created shortly before or after Susini’s death—executed with precision according to his designs, but not necessarily by his own hand.