Mechanisms of Power – Regina José Galindo

First floor

Tierra / Earth, 2013

Photography, Video, 35:56 min

Les Moulins, France

– ¿Cómo mataban gente? –preguntó el fiscal.

– Primero ordenaban al operador de la máquina, al oficial García, que cavara un hoyo. Luego los camiones llenos de gente los parqueaban frente al Pino, y uno por uno, iban pasando. No les disparaban. Muchas veces los puyaban con bayoneta. Les arrancaban el pecho con las bayonetas, y los llevaban a la fosa. Cuando se llenaba la fosa dejaban caer la pala mecánica sobre los cuerpos.

Guatemala vivió durante 36 años una de las más sangrientas guerras. Un genocidio, éste dejó más de 200,000 muertos. El ejército que peleaba contra la insurgencia definió como enemigos internos a los indígenas aduciendo que simpatizaban con la guerrilla y durante cruentos períodos se dedicó a perseguirlos. Con la intención de quedarse con las tierras (bajo la complaciente mirada de la oligarquía nacional) y la justificación de que los indígenas eran enemigos de la patria, el Estado puso en práctica la tierra arrasada. Esta fue una práctica común y característica del conflicto armado guatemalteco. Tropas de soldados del ejército y de las patrullas de defensa civil llegaba a las comunidades indígenas y destruían cualquier cosa que pudiera serles de utilidad para sobrevivir: comida, ropa, cosechas, casas, animales, etc. Quemaba todo. Violaba, Torturaba. Asesinaba. Muchos cuerpos fueron enterrados en fosas comunes que hoy forman parte de la larga lista de evidencias que confirman el hecho.

El anterior testimonio narra una de las formas en que el Ejército construía las fosas previo a asesinar y tirar los cuerpos dentro y fue escuchado durante el juicio por genocidio contra Ríos Montt y Sánchez Rodríguez. Guatemala 2013.

“How did they kill people?”, the public prosecutor asked.

“First they ordered the machine operator, Officer García, to dig a hole.

Then they parked lorries filled with people in front of El Pino and they filled the hole one by one. They didn’t shoot them. Often they jabbed them with bayonets. They tore open the chests with bayonets, and carried them to the pit. When the pit was full they let the power shovel fall onto the bodies.”

For 36 years Guatemala experienced one of its bloodiest wars. It was a genocide that left more than 200,000 people dead. The army that was fighting the insurgency described the indigenous people as internal enemies, claiming they were sympathisers with the guerrillas, and it spent several bloody periods of the war persecuting and murdering them. With the intention of taking their land (under the approving look of the countrys oligarchy), using as a justification the claim that the indigenous people were enemies of the fatherland, the state practised a ‘tierra arrasada’ (‘scorched earth’) policy. This was a common practice, characteristic of Guatemala´s armed conflict. Troops of soldiers from the army and civil defense patrols would arrive in indigenus communities and destroy everything that people might need to survive: food, clothing, harvests, houses, animals, etc. They burnt everything. They raped. They tortured. They killed. A lot of bodies were buried in mass graves that today are part of the long list of evidences that confirm the facts.

This testimony tells one of the ways the army dug pits prior to killing people and then tipping the bodies into the pits. It was heard during the genocide trial of Ríos Montt and Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez in Guatemala City in 2013.

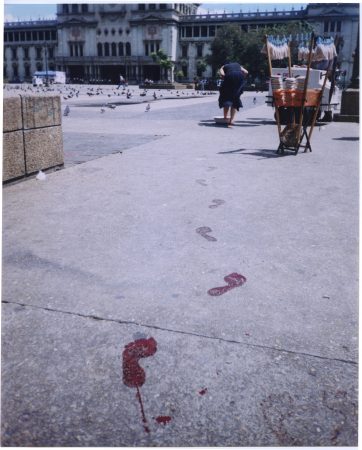

¿Quién puede borrar las huellas? / Who Can Erase The Traces?, 2003

Video, 37:30 min

Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala

Caminata de la Corte de Constitucionalidad hasta el Palacio Nacional de Guatemala, dejando un recorrido de huellas hechas con sangre humana, en memoria de las víctimas del conflicto armado en Guatemala, en rechazo a la candidatura presidencial del ex-militar, genocida y golpista Efraín Ríos Montt.

A walk from the Constitutional Court to the National Palace of Guatemala; leaving a trail of footsteps made with human blood. In memory of the victims of the armed conflict in Guatemala and in rejection of the presidential candidacy of the military, genocidal and former coup supporter Efraín Ríos Montt.

Paisaje / Landscape, 2012

Photography, Video, 24:50 min

Biennal de Arte Paiz, Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala

“El peligro de la belleza es su apariencia. Y el peligro del paisaje es que se traga la realidad – sublima la miseria.” – Mario Monteforte Toledo

De espalda vemos la vida pasar. De espalda esperamos la muerte. De espaldas, junto a un hombre que excava una fosa, permanece de pie una mujer. Nunca se ven, él cava un agujero, un vacío, ella recibe la tierra que empuja la pala hasta quedar enterrada.

“The danger of beauty is its appearance. And the danger of landscape is that it swallows reality – she glorifies the misery.” – Mario Monteforte Toledo

With our backs turned we see life pass by. With our backs turned we wait for death. With her back turned, next to a man who is digging a grave, stands a woman. They never see each other, he digs a hole, an empty space, she receives the earth thrown up by the shovel, until she is buried.

Caparazón / Shell, 2010

Photography, Video, 5:37 min

MADRE. Museo D’Arte Contemporane Donna Regina, Napoli, Italia

El miedo en su forma sonora, en cada estallido, en cada golpe. Mi cuerpo desnudo permanece en posición fetal dentro de un domo blindada. Un grupo de individuos, armados con palos, golpea frenéticamente el domo hasta destrozar sus propias armas.

Fear in its sonic form, in every explosion, in every hit. My naked body lies in a fetal position under a sealed dome. A group of people armed with sticks frantically beat the dome until their weapons are broken.

Perra / Bitch, 2005

Photography, Video, 5:25 min

Prometeo Gallery, Milano, Italia

Escribo la palabra PERRA con un cuchillo sobre mi pierna derecha. Una denuncia de los sucesos cometidos contra mujeres en Guatemala, donde han aparecido cuerpos torturados y con inscripciones hechas con cuchillo o navaja.

I write the word PERRA (BITCH) with a knife on my right leg. In condemnation of the acts committed against women in Guatemala, where tortured bodies have appeared with inscriptions carved into them with the blades of knives.

No perdemos nada con nacer / We don’t loose anything by being born, 2000

Photography, Video, 2:04 min

Segundo Festival del Centro Histórico, Guatemela

Metida en una bolsa de plástico transparente, como un despojo humano soy colocada en el basurero municipal de Guatemala.

Put in a clear plastic bag, like human rubbish, I am placed in the dump of Guatemala City.

Piel / Skin, 2001

Photography, Video, 14:46 min

49. Bienale di Venezia, Venezia, Italia

Me rasuro absolutamente todos los pelos y cabello del cuerpo, camino asi por las calles de Venecia.

I shave off absolutely all the hair on my body; I walk through the streets of Venice like this.

Hilo de tiempo / Thread of Time, 2012

Video, 18:30 min

San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, México

Hay que ir hacia atrás en el hilo del tiempo para encontrar la razón de tanta muerte y encontrar así la vida. Mi cuerpo permanece oculto dentro de una bolsa tejida para cadáveres. El público es libre de ir deshilando la bolsa hasta descubrir el cuerpo.

You have to go back in time to find the reason for so much death and thus to find life. I remain hidden in a bag woven for corpses. The public is free to gradually unravel the bag until the body is uncovered.

Falso león / False Lion, 2011

Guatemalan Gold

En el 2005, gano el León de Oro como mejor artista menor de 35 años en la 51 Bienal de Venecia. En 2007 vendo el León de Oro al artista español Santiago Sierra, quien a su vez lo revende a un coleccionista. En 2011 encargo una copia exacta del León de Oro a mis amigos escultores, Angel y Fernando Poyón de Guatemala. Ellos me entregan una copia exacta fundida en bronce con baño en oro guatemalteco.

In 2005 I won the Golden Lion as best artist under 35 years at the 51st Venice Biennale. In 2007 I sold the Golden Lion to Spanish artist Santiago Sierra, who in turn sold it to a collector. In 2011 I ordered an exact copy of the Golden Lion from my sculptor friends, Angel and Fernando Poyón, in Guatemala. They gave me an exact copy, cast in bronze and coated in Guatemalan gold.