The Bots, 2020

Video installation

Actors and actresses: Irina Cocimarov, Jesse Hoffman, Jake Levy, Alexandra Marzella, Ruby McCollister, Bobbi Salvör Menuez

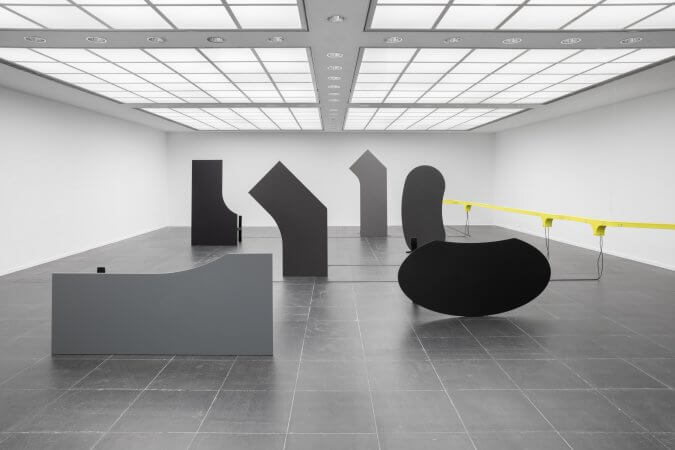

Six customised OKA desks, monitors, videos, headphones, cables

Dimensions and length variable

Courtesy the artists and Apalazzo Gallery

For The Bots, Eva & Franco Mattes collaborated with investigative journalist Adrian Chen and actors and actresses Irina Cocimarov, Jesse Hoffman, Jake Levy, Alexandra Marzella, Ruby McCollister, and Bobbi Salvör Menuez. They present anonymous testimonies from content moderators who have worked for Facebook in Berlin. Six videos have been created. In the room, visitors observe raised tabletops that form a minimalist installation. These tabletops are a reference to the furniture found in the Berlin moderation centre where the interviewees worked. The videos become visible to viewers only when they step behind the erected barrier and look behind the surface of the work.

What do we know about the mechanisms and regulations of social media channels that we use daily? Which contents remain visible and which are filtered out? And are there clear guidelines according to which content is deleted?

The films were executed with the typical aesthetic and features of online make-up tutorials. The statements in the films are derived from investigative research and interviews conducted with numerous witnesses employed as service providers for Facebook. The films were interpreted by actors so as to anonymise the statements of the content moderators. They perform the role of influencers addressing their followers directly. They recorded the videos using smartphones, for which reason the images are in portrait format. Advice on make-up products alternates with distressing descriptions of moderators’ work.

Content on social media channels is subject to restrictions and is thus scrutinised and monitored. Platforms claim to regulate their content through community guidelines. Some channels like Telegram also allow uncensored and problematic content. The guidelines cannot prevent thousands of ‘prohibited’ content from being posted online daily, however: violence, sexual assaults, hate speech, terrorism and pornography are just some of the categories of unwanted content on social media. Most of this content we cannot see, as it is deleted beforehand. This critical review is always carried out by human beings, i.e. it is not an automated cleansing process performed by algorithms. While programs filter content that appears to violate the guidelines of the respective platform, they cannot usually provide an independent interpretation of a post’s specific context.

In their work The Bots, Eva & Franco Mattes explicitly draw attention to the fact that critical content is seen and processed in large quantities by individuals. They are not bots, nor programs, but humans. They are called ‘content moderators’, and their profession falls within the category of ‘unregulated’ jobs that have emerged with the rise of tech companies (e.g. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk).

In the case of crowd-sourced job placement, content moderators often do not know themselves which companies they are working for. They are employed by so-called contractors who broker between tech giants like Google, Meta, YouTube, Twitter and the employees. In this way, the anonymity of the companies is preserved, their legal responsibility minimised and protected by non-disclosure agreements. Working conditions are neither publicly debated nor politically regulated. Services are governed by temporary employment contracts and are minimally paid.

Thanks to investigative journalism, reports on misconduct have nevertheless repeatedly reached the public domain in recent years. Journalist Adrian Chen was the first to shed light on the topic with his 2014 article in Wired titled ‘The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed’. Eva & Franco Mattes have been collaborating with Chen for years.

One of the main problems is that content moderators have to review thousands of posts daily before deleting them. Beheadings, child pornography, explicit violence of all kinds, fanatical hate speeches, and many other expressions of the depths of human depravity, as well as the sheer flood of banal uploads, leave in their wake trauma and profound disturbance in people.

While guidelines exist on the classification of objectionable content, these are not made public and must be kept secret by content moderators. The regulations are subject to daily changes. In order to quantify the moderators’ performance, a minimum deletion rate of 95% of the contributions must be achieved, otherwise the employee is sacked. According to anonymous statements made by employees, workers are monitored and under intense pressure to perform.

In many cultures, the rules are adapted to fit the locally prevailing conception of morality. Also, content moderation is often carried out by workers in the Global South, Asia and former colonies. The reason for this, apart from unregulated labour law, is a command of Western languages and an awareness of Western moral sensibilities.

However, even moderators are not objective filters. Despite guidelines, the process is subjective, influenced by individual interpretations. Content is removed, for example, when it is deemed politically or ideologically inappropriate. One’s own political leanings can potentially influence moderation decisions.

Through their choice of aesthetic, Eva & Franco Mattes create a deliberately jolting break with the content. They employ the staging of make-up tutorials for their artistic work. Political content is camouflaged to avoid censorship. This approach derives from activists who use this method to bring political messages and human rights violations in autocratic states to the public’s attention. It was the young TikTok user and activist Feroza Azis who filmed herself putting on make-up a few years ago in order to circumvent the censorship of the Chinese government. This enabled her to speak freely about the systematic repression and surveillance of Uyghurs in northwest China before she was blocked from the platform.

At the same time, make-up as a subject is to be understood symbolically. As the artists themselves say: ‘Make-up is a way of concealing imperfections in our faces, not much different from content moderation, which beautifies the surface of the internet by removing unwanted content.’