Edgar Honetschläger

GoBugsGo, 2018

Videoanimation, 1:29 min

C-Prints, various sizes

Courtesy the artist

Edgar Honetschläger (*1967) is an artist and filmmaker. In his artistic practice, he concentrates on questioning cultural givens and humankind’s relationship with nature. Influenced by personal experiences, his focus was increasingly directed at the effects of climate change and species extinction, which can no longer be ignored. For several years he lived and worked in Tokyo, where in 2011 he witnessed the Fukushima nuclear disaster and its dramatic impact on his friends and nature.

Honetschläger decided to not only raise his voice as an artist, but also as an activist, and to no longer only operate in the symbolic space of artistic production. With the creation of a nonprofit organization in 2018, he is committed to finding fellow campaigners worldwide. Against the background of the drastic development that in the past twenty years the number and variety of insects has dramatically declined globally, Honetschläger acts with the desire to regain habitats and permanently secure them, whether through donation or purchase, for the GoBugsGo campaign and transforming them into a space free of people.

The overarching vision of this nonprofit organization is the recovery of habitats for natural processes that are subject to little or no human influence.

To achieve this, Honetschläger finds fellow campaigners in the various representatives of public life; he goes to local authorities, to political representatives, devises contract models with law firms that aim to ensure the permanent safeguarding of land for non-commercial use and collective ownership on the basis of various international legislation.

The name GoBugsGo is a humorous incitement aimed at the insects—they are thus declared protagonists and agents. Despite the apparent levity of the campaign, Honetschläger formulates decidedly political and ethical imperatives. They place him in the tradition of large nature conservation associations, which also pursue land purchase as the only effective protection strategy from exploitation.

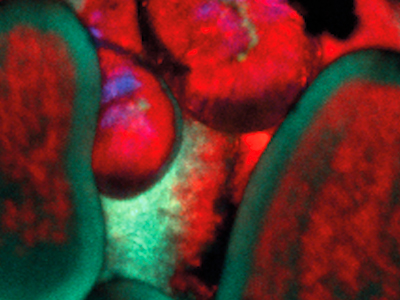

The “ground” actually represents the uppermost layer surrounding our planet. It consists of different layers and the uppermost one is only 20-30 cm thick. It is a living system formed over millions of years by the interactions between numerous biotic and abiotic factors. In this uppermost layer are symbiotic communities of microorganisms, animals, and plants that together create material cycles from which the fertile humus layer is formed. The “ground” is a living body worthy of protection that does not yet as such occupy the necessary space in public discourse that this fragile ecosystem requires.

The association GoBugsGo is open to any form of participation and any kind of engagement. In addition to financial contributions, participants can takeover activities such as PR work, programming, administration, and membership administration on a grassroots basis. The idea of an international network is based on people’s skills in their respective living environments and spheres of activity. Honetschläger has consequently managed to involve geologists, biologists, and ecologists who contribute their expertise in the selection and appraisal of potential plots of land. The project, which has been running for a year, is already active in Austria and Italy, where the artist has built up a strong personal network.

With his work, Honetschläger represents an expansion of artistic practice and the concept of art in the context of current ecological discourses. His project builds on the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century in which art, as a political commitment, sought to transform society from within. In contrast to this, however, Honetschläger does not focus on the idea of social sculpture, in which people want to change the social space for interpersonal action through collective participation, but with GoBugsGo targets concrete areas that should be seized from humans, so that ecosystems can develop there in a new form.

In a reversal of dependencies, GoBugsGo does not see humans as creators but as beneficiaries of their environment. The scale of population growth, the exploitation of natural resources, other fellow living beings, and even new technological possibilities have in part brought about massive destruction, pollution and the displacement of habitats and species—a transformation that will eventually becomes a threat to humankind. Scientists remind us that biodiversity would increase over the years if humans became extinct; if the insects die out, however, the decline of all flora and fauna would occur within a few decades.

Further informations: gobugsgo.org

Edgar Honetschläger (*1967 in Linz, Austria) is an Austrian filmmaker, artist and environmental activist. From 1985 until 1989 Honetschläger studied economics and art history at the universities of Linz, Vienna and Graz as well as at the Art Institute in San Francisco. Since then he has given numerous lectures, including at Gejutsu Daigaku University in Tokyo, the University of Yamaguchi and the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Honetschläger currently lives in Austria and Italy.

In 2004, Honetschläger founded the EDOKO Institute Film Production Vienna and was a founding member of RIBO Ltd. Tokyo together with Yukaki Kudo. In 2018 he set up the non-profit organization GoBugsGo, which works to preserve the habitat of insects.

Edgar Honetschläger has lived in New York, Tokyo, Rome, Palermo, Brasília and San Paolo. As a filmmaker and visual artist, he was invited to participate in exhibitions in Europe, the USA and Japan. His works were presented in 1997 at the documenta X in Kassel, curated by Catherine David, or in 2001 at the Kunsthalle Wien and in 2016 at the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma.

The exhibition presents GoBugsGo in Germany for the first time, dedicating a space to Honetschläger, where his activist project is presented alongside a historic insect collection from the the Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung.

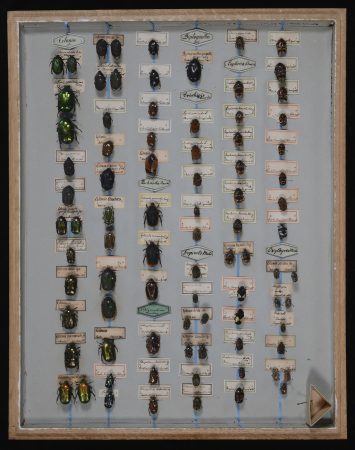

Collection of prepared bugs in systematic arrangement

around 1880

ex coll. Universität Heidelberg

On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Inside the display cabinets are 42 insect boxes. They are part of a collection that was originally created in Heidelberg sometime before 1880 and was later merged with the collection of the Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung. The beetles come from different regions of the world; they have been arranged in an orderly manner and represent a small sample of the diversity of species. The procedure for creating such collections included capturing the animals, killing them with ethyl acetate, and then positioning them, impaled on insect pins, in geometric rows and boxes. The ordering principle was a classification according to their forms and variants. Thanks to such historical collections, it is now possible to identify locally extinct species that have been lost since then. They represent the human fascination with the variety of forms and colors of living things. Such collections were and continue to be common practice throughout the world for preserving the beauty of natural living things for the next generation and documenting biodiversity.

Insects are a significant part of the food chain in terrestrial ecosystems. They are the most biodiverse animal group. In the course of evolution, the behavior and appearance of the myriads of existing species have adapted to very particular conditions. Sometimes they are the key to the existence of other living organisms, and yet they in turn are simultaneously dependent on certain plants and climatic conditions. The absence of individual species can affects entire chains of other living organisms. In nature, everything is inextricably linked by invisible bonds, and it is important to understand these relationships. The complexity of the causalities and dependencies between living organisms is not always known to humankind, and yet we intervene in their habitats nonetheless.

There is a new awareness of the importance of insects, but mostly from the perspective of their (bio)economic value for human civilization. This approach denies our fellow living organisms—both animals and plants—their integrity, and renders them subservient to humankind. There is no intrinsic value ascribed to living organisms; a reductionist view prevails. The belief that our culture and civilization is governed only by reason and the economy needs to be broadened. Our emotions regarding the destruction and irreversible loss of “nature” should not lead us to capitulation. On the contrary, it is about the ability to recognize ourselves as part of a complex and living world, as well as finding new approaches to human activity.