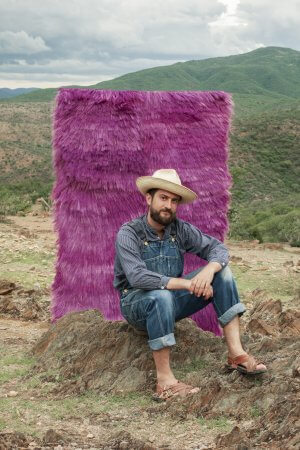

Fernando Laposse

Pink Hammock, 2019

Hammock, woven sisal, dyed pink

200 x 400 x 100 cm

Dog benches (pups), 2023

Weaven agave fibers, plywood structure

Each 67 x 40 x 45 cm

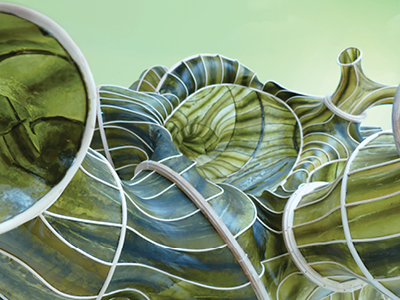

Totomoxtle, 2023

Polygonal multi-colored corn panels

12 m2

Agave Regeneration, 2019

Video

5:34 min

Totomoxtle – Biomaterial Made from Mexican Heirloom Corn Husks, 2019

Video

7:19 min

Courtesy Fernando Laposse

Fernando Laposse views art as a socio-ecological action. For Bending the Curve, the Mexican artist has conceptualized a room installation spanning over 140 square meters, in which the products of the indigenous Mixteco community are presented as exhibits in a staged landscape. Laposse founded a cooperative with them in the rural area of Tonahuixtla, where he combines local knowledge, ecological restoration, social community life, and sustainable economic practices. The artist revitalizes fallow areas, prevents soil erosion, and advocates for food sovereignty and the protection of cultural plant diversity and indigenous knowledge.

In this exhibition, Fernando Laposse focuses on two natural materials from Tonahuixtla: corn leaves and sisal fiber. These natural products are collectively produced, processed in the traditional manner in the cooperative, and transformed into contemporary artworks when placed in a museum context. The colorful Totomoxtle intarsia panels made from corn leaves are displayed on the wall. The Pink Hammock and the three sculptural dog benches (pups) are crafted from sisal fiber derived from agave plants. The two films, Agave Regeneration and Totomoxtle – Biomaterial Made from Mexican Heirloom Corn Husks, reveal the history of the artworks and the Tonahuixtla community.

Laposse began collaborating with the indigenous Mixteco community in Tonahuixtla in 2015. The rural village is located less than 50 kilometers from the world’s oldest archaeological site of maize domestication—a plant that has always played a central cultural and financial role in the community’s identity. The history of this place is marked by socio-ecological challenges that began in the 1990s with the introduction of hybrid maize seeds and the abandonment of traditional farming methods. This development led to a range of problems, including soil erosion, migration, unemployment, and the loss of agrobiodiversity and endemic plant species, especially maize.

Tonahuixtla is not alone in its history; it exemplifies the fate of countless rural communities in South Asia and Latin America affected by the spread of new agricultural systems. In Mexico, agricultural modernization began in the 1950s with a focus on increasing domestic demand. This led to the intensified use of high-yield but less resilient and adaptable industrial seeds that rely on expensive synthetic fertilizers, pesticides and machinery. In just a few years, Mexico lost 80% of its maize diversity. The consequences of these changes were particularly severe in Tonahuixtla, where the soils were severely depleted, and many residents became dependent on large corporations, leading them to emigrate to the United States to make a living.

Laposse, who had been visiting the Tonahuixtla community since childhood, returned there after studying art in London to find a village on the brink of extinction. To signal change and hope for the community, he initiated Totomoxtle: a socio-ecological artistic project aimed at reintroducing native maize varieties in collaboration with local families who had preserved traditional seed varieties for generations and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) seed bank in Texcoco, Mexico. In just four years, more than 50 people were employed, and six endangered maize varieties were reintroduced into local agriculture. Working together with the cooperative he founded, Laposse used the colorful leaves of criollo maize, usually agricultural waste, to create intarsia for furniture and interiors. The name of this new material, Totomoxtle, refers to the indigenous Nahuatl word for corn husks. It is veneer, 0.5 to 8 mm thick sheets, typically made from wood and, in this case, from maize farming remnants. After being cut from the plant, corn leaves retain their color and can be flattened or bent due to their fiber structure. The production of Totomoxtle created jobs locally and motivated the community to return to traditional farming practices. Craftsmanship became a driving force for socio-ecological transformation on a small scale.

In a second step, Laposse and the cooperative sought a solution to the severe problem of soil erosion, leading to the reintroduction of agave plants on a 120-hectare area. Up to 150,000 agaves were planted. Their roots can anchor to rocks, preventing soil erosion, storing water in dry soil, and strengthening ecosystem resilience. However, the use of agave plants in Tonahuixtla differs from their typical use in Mexico. Agaves are usually grown industrially to produce the national spirits Mezcal and Tequila. For this, the agave plants are cleared from the fields, and their leaves are left as waste, leading to insect infestations and potential soil harm from excess leaves. In Tonahuixtla, the agave plants are preserved. Only their leaves are harvested and ground to obtain sisal fibers, which are woven into textile sculptures. The three dog benches (pups) sculptures at the Frankfurter Kunstverein showcase the natural “blonde” color of sisal. In contrast, the Pink Hammock sculpture was dyed with a natural pigment. The red pigment cochineal is produced by a beetle that lives on cacti in Central America.

In Laposse’s reforestation project with agaves, the production of textiles from sisal becomes an act of care that distances itself from the conventional textile industry, which depletes natural resources faster than they can regenerate. Laposse’s communal practice goes beyond sustainability, regenerating ecosystems and communities to preserve local biocultural wealth for future generations. He demonstrates the regenerative power of art to address complex issues and shows how art can provoke not only aesthetic but also socio-ecological transformation. Laposse acts in favor of a financially independent community that operates in harmony with the local ecosystem. Landscape and people join up in Tonahuixtla in an ecologically oriented economic cycle, underscoring the importance of awareness and promoting change, not matter at what level it occurs.

The presentation of Fernando Laposse’s work in the exhibition Bending the Curve exemplifies a whole range of artists who use their art to advocate for the preservation of agrobiodiversity and a shift in agricultural practices through local solutions and research approaches. This includes artists like Vivien Sansour with the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, Marwa Arsanios with her film trilogy Who is Afraid of Ideology?, Jumana Manna with her films Foragers and Wild Relatives, Nida Sinnokrot with the residency program Sakiya – Art/Science/Agriculture, as well as the artist duo Cooking Sections with their art research projects CLIMAVORE and Monoculture Meltdown.

BACKGROUND ON THE FOOD SYSTEM

The climate crisis confronts our food system—agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture—with new challenges, such as rising temperatures, wildfires, droughts and floods. What we eat, how much food costs, where land can be cultivated, and how much food people have access to are closely tied to biodiversity and increasingly extreme climate conditions. An essential part of biodiversity is genetic diversity, which allows species and populations to adapt to constantly changing environments. This also opened up a wide range of options of plants for people to use and grow.

The diversity of organisms living in our agricultural ecosystems is referred to as agrobiodiversity. This includes crop plants, livestock, microorganisms and wild plant species. It is largely a cultural heritage created by humans over centuries, making it a unique form of biodiversity. Agrobiodiversity encompasses not only agriculture and food but also history, tradition, identity, culture, geography, genetics, science and craftsmanship. As the genetic foundation for food and agricultural production, our future depends on it. Agricultural diversity enhances the overall resilience of our food systems, allowing for the breeding of more resistant plant varieties that can better withstand challenges like diseases, pests, changing environmental conditions and other threats. Due to global warming, increasingly harmful pathogens that destroy crops and wipe out entire plant species are spreading. However, today, agrobiodiversity is under significant threat, and so is their contribution to the future of human nutrition.

Like the climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis is human-made. The most significant loss of agrobiodiversity began in the 1960s when scientists attempted to improve global food security by increasing the yields of wheat, rice and maize. To cultivate the additional food needed urgently, thousands of traditional varieties were replaced by a small number of new varieties (especially in maize and soybeans). These hybrids were bred using a mix of traditional and genetic engineering methods. The strategy that guaranteed this using new technologies—new seed varieties, more agrochemicals, increased irrigation—became known as the “Green Revolution”. This movement was supported by various organizations and scientists, including the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation, as well as agricultural scientists like Norman Borlaug. The Green Revolution spread worldwide, especially in South Asia and Latin America, and marked the beginning of modern industrial agriculture in countries of the Global South. The introduction of hybrid varieties was often associated with intensive use of agrochemicals – fertilisers and pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, fungicides). Just four agrochemical companies control 60% of the global seed market (and 75% of the pesticide market); these companies thus represent huge market power. The dependence on hybrid varieties, fertilisers and pesticides, and in the hands of a few corporations, has often left local communities of small farmers in financial difficulties, losing their resilience and traditional agricultural knowledge. While new practices and new scientific knowledge have alleviated acute hunger problems in many regions, biodiversity, local food systems, social justice and the health of soils, ecosystems and water bodies have taken a back seat. The Green Revolution spread worldwide, particularly in South Asia and Latin America, marking the beginning of modern industrial agriculture in countries of the Global South. The introduction of hybrid varieties sometimes intensified the use of agrochemicals—fertilizers and pesticides (herbicides, insecticides, fungicides). Only four agrochemical companies control 60% of the global seed market (and 75% of the pesticide market); these companies thus represent huge market power. Due to their reliance on hybrid varieties, fertilisers and pesticides and in the hand of a few corporations, local small-scale farming communities often faced financial difficulties, losing their resilience and traditional agricultural knowledge. While the new practices and scientific knowledge were able to alleviate acute hunger issues in many regions, in the long run they sidelined biological diversity, local food systems, social justice, and the health of soils, ecosystems and water bodies.

In response to the negative effects of globalization and industrialized agriculture, protest movements by farmers, agricultural laborers, and indigenous communities emerged in the 1990s, opposing industrialized global agriculture and prioritizing local solutions. They propagated the concept of food sovereignty, which challenged the dominant model of food security as a priority. Food sovereignty refers to the right of individuals and communities to have control over their own food systems, including how food is produced, distributed and consumed. The focus is on local and traditional knowledge and sustainable agricultural practices (agroecology).

Today, several plant species familiar to us from our daily lives are affected by the loss of agrobiodiversity. A well-known example is the story of bananas. Of the over 100 species of Musa paradisiaca (banana) that evolved through natural selection, the seedless Gros Michel was grown and spread worldwide. After Gros Michel plantations were nearly wiped out by a soil fungus, the industry turned to a fungus-resistant variety: the Cavendish banana. However, as a single variety, it is susceptible to new fungi and pathogens at any time. More and more plants that have been reduced to a few varieties are exposed to the dangers caused by climate change: popular examples include Hass avocados, Arabica coffee, cocoa, as well as apples and potatoes, and many more. But above all, plants on which global nutrition depends are at risk of losing their diversity: wheat, rice, and maize. With many farming systems optimised for high yields, people today have major challenges – yields and profits have been optimised in the short term, but in the long term the diversity, resilience and robustness of the farming system has been undermined.

However, there are good opportunities to improve the agricultural system again. In parallel with the Green Revolution, there have been efforts worldwide for decades to preserve species and variety diversity in gene or seed banks. Seed banks are a resource for maintaining at least part of the historically grown agrobiodiversity; with great potential for future food security. There, researchers can find populations and old varieties to breed more climate- or pest-resistant varieties that are better able to cope with current environmental changes, now and in the future. There are now approximately 1,700 seed banks worldwide that house collections of plant species, invaluable for scientific research, education, conservation, and the preservation of indigenous cultures.

The concept of gene banks has proven moderately successful in rescuing staple foods, but it has been much less successful for vegetables and fruits. And while storing seeds under carefully controlled conditions is not easy but feasible, many foods like coffee, apples, peaches and vanilla must be preserved as plants or trees, posing an even more complex and expensive challenge. One solution could be to bring diversity from seed banks back to the fields of farmers, where old varieties can once again become part of the diversity of varieties and further develop our agrobiodiversity.

In the future, we will need a variety of different approaches to have enough good, healthy food available. On the one hand, we need highly productive varieties grown in climatically favourable conditions on good soils, as in Ukraine; this plays an important role in global food security. On the other hand, we need to use local and indigenous knowledge, rediscover traditional varieties and develop them further. It is of great advantage to use techniques that mimic nature, that rely on varietal diversity, diverse crops and landscape diversity, as well as natural pest control. Applying traditional knowledge does not mean going back to the past; it means looking at the various food systems that people have preserved for millennia in harmony with nature and considering how these practices can best be applied and developed within local approaches in the modern 21st-century food system.

Fernando Laposse (*1988, Paris, FR) is a Mexican artist with a degree in product design from Central St. Martins in London (UK). Today, he resides and works between Mexico City (MX) and Tonahuixtla (MX), where he has been collaborating on social-ecological projects with the Mixtec community since 2015. The works created in collaboration with them have been exhibited in numerous international museums and festivals, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York (US), the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (UK), the Triennale di Milano (IT), the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York (US), the World Economic Forum in Davos (CH), and the Dutch Design Week in Eindhoven (NL). He has been nominated for numerous international awards and won the Future Food Design Award 2017 from the Dutch Institute of Food and Design in Eindhoven (NL).