Pflanzensoziologisches Institut

Prepared ash tree, 1999

100 x 640 cm

Courtesy Dr. Edith Zewell

Prepared winter dandelion, 1997

400 x 40 cm

Courtesy Dr. Roland Eberwein

Drawings by Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Erwin Lichtenegger

(left wall)

Tanne (Abies alba), 1998, 72 x 56 cm

Zuckerrübe (Beta vulgaris), 2003, 62 x 27 cm

Wiesen-Schwingel (Festuca pratensis), 1969, 62 x 39 cm

Kraus-Ampfer (Rumex crispus), 1958, 53 x 30 cm

Acker-Winde (Convolvulus arvensis), 1957, 58 x 12 cm

(right wall)

Fichte (Picea alba), 1998, 83 x 50 cm

Stiel-Eiche (Quercus robus), 1998, 49 x 60 cm

Berberitze (Berberis vulgaris), 1998, 48 x 49 cm

Kopfsalat (Lactuca sativa), Jahr unbekannt, 39 x 54 cm

Courtesy Dr. Hilde Lichtenegger

Drawings and plant specimens in the exhibition The Intelligence of Plants come from the extensive collection of the Pflanzensoziologisches Institut (Klagenfurt, AT), which is headed by botanist Dr. Monika Sobotik. The Austrian Pflanzensoziologische Institut (Institute for the Sociology of Plants) deals with plant-sociological and root-ecological issues.

The name of the institute refers to the discipline of plant sociology. This is a systematic research method of geobotany and the study of the socialisation of plant species. One focus of plant sociology is the study of site conditions and the interaction between species. The term plant sociology was also used by sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour as a model of thought, as it aims to describe and understand societies made up of heterogeneous components, which this natural science, according to Latour, can serve as a metaphor for the social sciences.

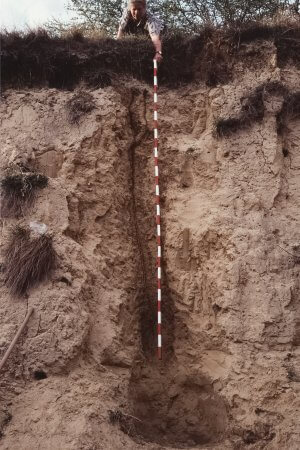

Since the 1960s, the researchers of the Pflanzensoziologisches Institut, Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Lore Kutschera, Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Erwin Lichtenegger and Dr. Monika Sobotik, have systematically and with extreme care excavated, photographed, documented, drawn and in some cases made preparations of the root systems of plants in their natural habitats. For these scientists, root research means uncovering roots as they grow in their natural environment and to which conditions they react individually. Lichtenegger drew the exposed roots as true-to-scale mapping, because this manual method allows a documentation that photographic documentation does not make possible. The drawings are unique instruments for making visible something that is otherwise not visible in its complexity. Down to the finest details, the drawings show the growth of the roots, so that a different perspective and an awareness of the dimensions of that part of the plants becomes comprehensible, which cannot be derived from the view of plants above the surface of the soil.

Today, researchers across disciplines recognise the central role and essential performance of plants for life on the planet and that a complex interplay of different species and geographical conditions is what makes biodiversity possible in the first place. One of the services plants provide is to transport elements from the air to the depths of the soil via their metabolism. Conversely, they release water and oxygen into the air, as well as numerous messenger substances that have only been rudimentarily researched today, which become part of the atmosphere and have an impact on the physiology of animals and humans. The fertile, uppermost humus layer is only created by the coexistence and metabolism of countless microorganisms, which create a living substrate in association with plants and their roots.

The mineral soil is kept stable by a branched network of roots, so that soil erosion caused by water, wind and earth movements is counteracted. At the same time, roots loosen soils and contribute significantly to the formation of humus. In symbiosis with fungi and bacteria, a complex interplay between organic and inorganic materials and living beings is thus created, the functions of which are currently being researched more and more and are recognised as existential for the continued existence of all species on earth.

With its work, the Austrian Pflanzensoziologisches Institut has created the basis for root-ecological questions. The visualisation of the space below the soil surface has structurally ordered ancient knowledge about plant communities. The research is based on the aim that by observing the root systems and the associated soils, it is necessary to understand not only the individual plant, but also its interaction in the network of entire plant societies. The research evolved with the understanding of the importance of plant diversity for fertile soils and a high occurrence of microorganisms with which the plants live in association.

At the Frankfurter Kunstverein, a prepared ash tree with its extensive root system (excavated by Dieter Haas and Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Erwin Lichtenegger), a prepared winter dandelion with its more than four-meter-long root and original drawings with illustrations of mapped roots of Central European wild and agricultural plants are on display.