Sonja Yakovleva, State of Strike

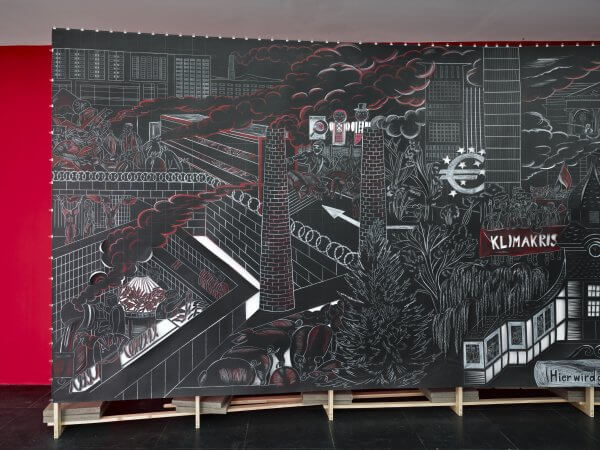

State of Strike, 2024

Paper cut and drawing, card stock, pencil and coloured pencil

10,65 x 2,71 m

Courtesy the artist

In Sonja Yakovleva’s new works, specially created for this exhibition, the overarching motif is the representation of an abstract power that governs bodies and is embedded in them.

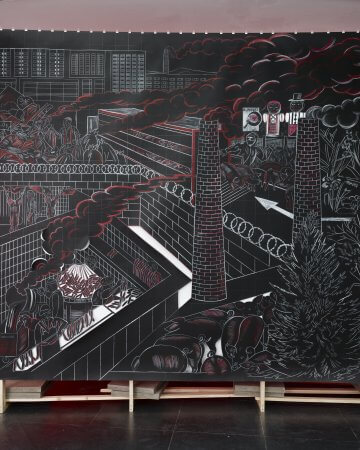

In State of Strike, the city itself is a body whose vital functions are maintained by various organs, and the blood in its veins are the workers who supply the living organism. Sonja Yakovleva depicts these people crowded together in the streets as they go on strike, utilising their bodies in public space. But pigs from industrial fattening farms are also freed and become part of the resistance against the exploitation of their bodies.

Yakovleva has created a mural over 10.5 metres long. It depicts a city in which e-commerce, the meat industry, delivery services, day-care centres, hospitals, construction sites, industrial cleaners and restaurants have been condensed into a very small space. She also deliberately incorporates recognisable Frankfurt buildings into her composition — the Alte Oper, the central railway station, the facades of brothels and the Sudfass-Beine. Some of the motifs were photographed by the artist in Frankfurt, and others come from online stock photography providers or Instagram. In the images’ composition, various locations in the post-industrial city, which are otherwise marginalised or made invisible, are placed at the centre.

The city is depicted here as a symbol of the modern age and society at large, with all the buildings representing different production sites. We see a dense flow of bodies going on strike. Yakovleva is driven by the contradictions of an increasingly flexible and yet insecure work environment. People, especially those with migrant backgrounds, are often forced to take on difficult jobs — characterised by poor working conditions. In her depiction, she shows us a city of delivery drivers, temporary workers, cleaners and meat industry employees. What would happen if not only the unionised workers, but they too were to go on strike? Would everything come to a halt? Who are all these people who keep the pulsating system of a city and a state functioning? In her mural, Yakovleva takes a close look at migrant workers and has them populate the city streets with their bodies. The artist also includes animals in the strike, because they too have lost self-determination over their bodies.

Through her thematic focus on the migrant strike of precariously employed workers, Yakovleva succeeds in raising the question of the relationship between body and politics in two different ways. On the one hand, how are workers’ bodies controlled and exploited in today’s precarious labour conditions? And on the other hand, how can these bodies become a new force by going on strike and opposing precisely this control and exploitation? And by going on strike, demands for solidarity and new forms of social organisation are brought to the streets by these protesting bodies.

Yakovleva’s working process is characterised by montage and collage, collecting and assembling. For Germany, 2023 and 2024 have been the years of nationwide waves of strikes. Not only for higher wages, but also for the implementation of climate protection measures. So for State of Strike, a variety of elements have been incorporated into the monumental mural: research into historical sources and literature on migrant strikes in the 1970s and the working conditions of precarious workers since the post-war period, interviews with e-commerce workers, the publication of the investigative collective “correctiv” in early 2024 and the remigration plans of right-wing networks. Through the social mobilisation against racism that soon followed, Yakovleva thought about a migrant strike as a means of protest against racist tendencies in society. During her research, she sifted out scenes and stories, contradictions and patterns from her own world of experience, which she incorporated into the themes of labour and strikes. She visualises the strike of migrants and workers, who represent a large part of the working class, and sets her monumental work of art against the fast-moving flow of information in the media.

For this new mural, Yakovleva quotes the visual language of various forms of propaganda art: the agit prop of the 1920s in Soviet Russia, the murales (wall paintings) of Mexico’s Diego Rivera and even street art. She uses isometric perspective, in which the image has no single vanishing point and in which the edges of components are drawn in abbreviated form. And through the use of collage and condensing visual elements, she depicts different scenes simultaneously , using geometric forms and the symbolism of colours —black, white and red.

This is the first time that Yakovleva has combined her characteristic technique of paper cutting with drawing. In her practice, the drawing is the central starting point for design and image composition, but it is lost in the act of cutting. Her pictures are created as drawings, which the artist rescales with the help of a grid and transfers to larger paper. In State of Strike, we see her painting skills, her mastery of lines, shapes and shading, her ability to observe and reproduce the world around her, her love of experimentation and her craftsmanship. Sonja’s drawings and papercuts thrive on the flattening of motifs and stage like perspective. Her style can be associated with the phenomenon of superflat, an artistic style that reacts to consumer culture in postmodern painting.

Yakovleva says of her choice of papercutting that she likes the cross-references to historical development. From the 17th century onwards, the papercut became popular in Europe as a time-saving and cost-effective substitute for portrait painting. And whilst painting was reserved for the aristocracy, the lower classes could have silhouettes made from the outline of a profile, which were offered by street artists.

In her work State of Strike, Sonja Yakovleva combines references to an artistic technique with socio-political questions — regarding the possible outcomes of going on strike, through which the invisibility of these precarious and often migrant forms of labour becomes visible. There is a sense of solidarity among the workers who go on strike, which provides strength to build alternative ways of living and working. These bodies, that otherwise work, deliver, pack, transport or wash up, become visible through the movement on the street.They become resistant bodies that withdraw their physical strength from exploitation, and instead, bundle it in the collective in order to protest against their exploitation and bring about change.