Up Next, 2023

Video installation, raised floor like in data centers

24:04 min

Courtesy the artists and Apalazzo Gallery

The Frankfurter Kunstverein is premiering Eva & Franco Mattes’ new video work, Up Next. This piece takes as its subject the fate of Fatemeh Khishvand (*2001, Tehran, Iran), who became known as Sahar Tabar on Instagram. Her story turned into a phenomenon of internet culture. The case of Fatemeh Khishvand touches on many themes that Eva & Franco Mattes explore in their work: visibility, misinformation, the dissemination of images, meme culture, virality, exploitation and manipulation.

Since 2019, the artist duo has been following the case of the Iranian social media celebrity and archiving thousands of related photos and articles. For the video slideshow, which is conceived entirely without sound, the artists have selected a hundred images: Tabar’s selfie photos alternate with unverified quotes from articles about the blogger, primarily clickbait articles that have spread mostly derogatory, contradictory, and at times false information about the Instagrammer.

In between the individual images, the artist duo inserts black frames, empty pauses. These are meant to give viewers time to reflect on the veracity of what they have seen. This stylistic device breaks with the speed of the mode on Instagram that sets the time limit for Stories and Reels. These may not exceed a maximum duration of 15 and 90 seconds respectively and are continuously played back without interruption. This is all part of a strategy inherent to social media. It was designed to generate neural reactions resembling addiction, triggered by the constant flow of new visual stimuli. This phenomenon is part of the so-called attention economy prevailing in the social media world and has permanently changed our viewing habits.

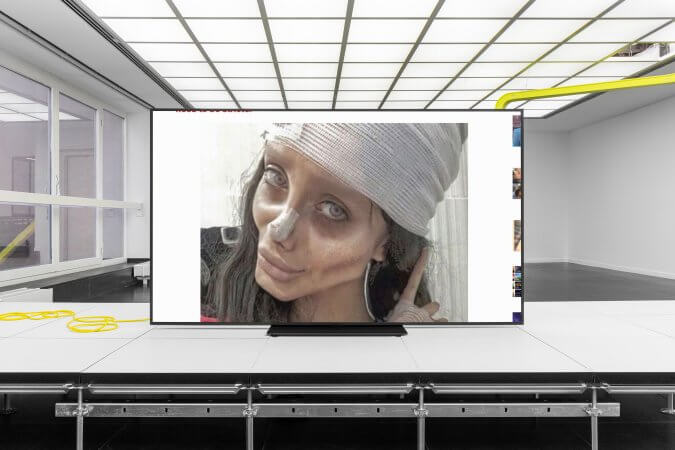

During peak periods, up to 486,000 people followed Tabar’s Instagram profile. She posted selfies showing herself with exaggerated lips, a pointed, snub nose, pale skin, brightly coloured hair, dark circles around her eyes and bony arms and legs. The resulting aesthetic drew similarities to costumes, zombies, or animated characters, such as Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride (2005).

Although the blogger mainly simulated this aesthetic by means of makeup, Photoshop, and filters, she was accused of using lip fillers, liposuction and rhinoplasty by the clickbait press and internet public. This led to a wave of outrage and scandalisation. These speculations were backed up by the citing of dubious sources.

Tabar’s profile garnered significant attention, especially when online gossip sites pointed out her resemblance to actress Angelina Jolie, dubbing her ‘Zombie Angelina Jolie’. They even claimed that she underwent up to 50 medical procedures to resemble the actress. This was just one of the many confusing statements that online tabloids posted, which then went viral.

Many of the media outlets reporting on the case never questioned whether it could be a parody and so a media hoax. Rather than discussing the plausibility of the case itself, the tabloid public became indignant over the young woman. It was precisely this outrage, surprise and uncritical attitude on the part of the online audience that turned Tabar into a global phenomenon.

What can be symbolically observed in this case is the power of misinterpretation and fake news as fuel for an online economy of excitement and scandalisation. Tabar herself declared her appearances as online selfie performances in the tradition of Cindy Sherman.

The staging of fictional identities is a recurring element in art. Cindy Sherman, for example, assumed the appearance of mostly female characters in her works from the 1970s to the early 2000s by arranging clothing, hairstyles and different visual contexts. On her current Instagram account, Sherman posts self-portraits that take the alterations of reality through modern filters to extremes. Younger artists, too, such as Amalia Ullman, have invented fictional identities on Instagram, confusing and entertaining an online audience in equal measure.

Historically, playing with pseudonyms has a long tradition: artists like Marcel Duchamp, whose alter ego was called Rrose Sélavy, Lynn Hershman Leeson with numerous fictional personalities, as well as Eva & Franco Mattes with the invented artist Darko Maver in 1998. His fictional life and works spread through the media and the art world. Maver’s career reached its media peak in 1999 with his invitation to the 48th Venice Biennale. Later, the artist duo declared publicly that both Maver’s life and his works were invented.

In their modern and contemporary form, these staged performances have developed into collective online performances in which millions of people participate every day on Instagram, in the form of photos and reels, stories and selfies, make-up tutorials and ‘outfits of the day’.

The media phenomenon surrounding the figure of Tabar led to a dramatic turn of events in real life. On October 22, 2019, the Iranian news agency Tasmin reported that Fatemeh Khishwand had been officially charged and arrested in Tehran on charges of ‘blasphemy, incitement to violence, illegal acquisition of property, violation of the national dress code and encouraging young people to corruption’.

This is not an isolated case. Since 2016, Iranian female influencers have been increasingly arrested for their online activities.

At the time of Khishwand’s arrest, Instagram was still permitted as a social media platform in Iran. Twitter and Facebook were already blocked by the government. However, anonymity and freedom of speech were not guaranteed on Instagram either. Given the current backdrop in Iran and the protests for women’s rights, Tabar’s story has gained in importance in the context of the significance of social media channels. From the Arab Spring onwards, these channels have played a central role in enabling civil disobedience, the networking of protesters and the dissemination of independent news.

Since 2011, social media has provided the opportunity for an open-source investigation that aims to document and denounce human rights violations. In autocratic states, such investigations are observed, restricted or blocked. At the same time, the Iranian government has learned how to use social media to its advantage, transforming it from a tool of information to one of disinformation, control, surveillance, and political manipulation – a means of restricting freedom. Sahar Tabar’s Instagram account was deleted at the time of her arrest. While her online persona remains visible, it is overshadowed and unrecognisable due to numerous fake news and fake profiles superimposed upon it.

Why do Eva & Franco Mattes take on this phenomenon? The two artists repeatedly raise broader questions about the authenticity of images and information, the staging and ambivalence that prevail in the digital sphere. The overarching theme is the manipulation of identity online and the way these fakes feed back into real-life society. Digital and analogue communication today form a single unit, indivisible and interwoven.