Walter R. Tschinkel

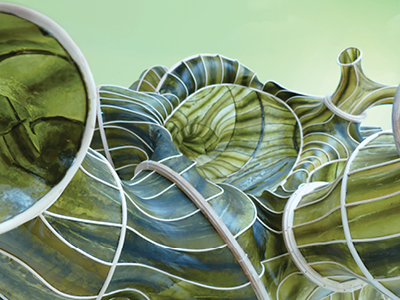

Six architectures of ant nests of different species Camponotus socius, Pogonomyrmex badius, Trachymyrmex septentrionalis, Formica Dolosa, Pheidole morrisi, Cyphomyrmex rimosus

Tin casting

Various sizes

Courtesy Walter R. Tschinkel

Walter R. Tschinkel is a US biologist who conducts research in the field of sociobiology and behavioral ecology of social insects, particularly ants. Tschinkel’s decades of work have contributed significantly to a deeper understanding of ants’ way of living. He has devoted special attention to their nest architecture. His studies have revealed how ants regulate temperature and humidity within their nests. The exhibition features six objects from Walter R. Tschinkel’s collection, which the scientist created for research institutions. The objects concerned are aluminum and tin casts of six underground nests. Each nest was built by a different population, all living in the same 30-hectare habitat in the sand dunes of the pine forests located on the coastal plains of North Florida. In this region, there are up to 50 different ant species living in hundreds of populations.

Walter Tschinkel’s interest lies with this specific space, which he calls “the ant paradise” because it allows him to reveal biodiversity. In this limited area, ants have developed various characteristics and abilities. For example, the Florida Harvester ant has specialized in collecting plant seeds and created a quite different habitat than the tiny Pheidole adrianoi, which lines its nest chambers with fungi. Nocturnal species can coexist with diurnal ants, specializing in different types of food; some collect caterpillar feces, while others gather dried insect parts to nourish their fungal gardens. Worker ant body sizes can vary by up to a hundredfold, as can colony sizes, meaning ants construct their nest architectures differently.

These various species share the same habitat and adapt in such diverse ways that they can coexist in an extended community.

The selection of casts in the exhibition illustrates how nature creates diversity and what exactly diversity is. At first glance, the architectures may appear different, but Tschinkel’s research reveals that nest-building ants create individual variations of the same basic plan. This basic structure—a vertical shaft with one or more horizontally connected chambers—traces back to the hunting wasp from which ants evolved.

Almost all modern ant nests follow this ancestral pattern. Diversity arises from many small modifications of a basic model.

Ants are essential beings for ecosystems due to their populations’ high adaptability and collective intelligence. They aerate soil, contribute to humus formation, dispose of dead organisms and parasites, distribute seeds, and cultivate fungal species in an act of symbiotic welfare. Scientists are increasingly interested in ants due to their biochemical bacterial film which protects them from diseases and fungal infections. They are true masters of recycling and logistics.

The Frankfurter Kunstverein often presents scientific specimens and artworks in shared spaces in its exhibitions. Both art and science can render insights and ideas physically experienceable through their actual manifestation. Visibility generates understanding.

Tschinkel’s cavity casts create a unique bridge between scientific specimens and sculptural objects. They condense knowledge based on many years of observation and data collection. Tschinkel does not view ants solely as objects of scientific curiosity, but as fellow inhabitants and co-creators of a shared world. In the exhibition, the nest casts serve as objects of knowledge and simultaneously as matter transformed by complex life processes, beings who have existed on this planet for millions of years.

INFORMATION ABOUT THE INDIVIDUAL ANT SPECIES REPRESENTED IN THE NEST CASTS

CAMPONOTUS SOCIUS

This is the largest ant species in Tschinkel’s area. When excavating their nests, the ants scatter the dug-out soil in a fan-like pattern, making their nest openings easily discoverable at the base of clumps of grass. The nests can be over a meter deep or as shallow as 30 cm, but they are always sturdy. Colonies have a single queen, who may inhabit up to 15 nests in the summer. Towards the end of the season, they abandon all but one or two nests for overwintering. The female workers usually forage individually for honeydew from aphids and mealybugs, bringing the liquid back to the nest. Like other Camponotus ants, their larvae pupate within a silken cocoon they create themselves.

POGONOMYRMEX BADIUS

One of the larger ant species found in the dry, sandy soils of the coastal plains from North Carolina to Mississippi. Their nest chambers are distinctive because the older workers in the area collect charcoal pieces and deposit them on the nest disc. The black nest disc stands out as a result from the white sand in which the nest is constructed. From April to November, older workers leave the nest at 8 am to collect seeds from up to 50 different plant species and prey insects. They deposit everything in the upper nest chambers, from where younger workers transport the collected items to lower chambers or to the larvae in the lower third of the nest. Since the seeds are too large for the ants to open, they wait for them to germinate. Germination varies depending on the season, species and soil temperature.

All ant populations exhibit strict division of labor. This is based on an ant’s age and runs parallel with its location within the nest. Young workers are born in the lower third of the nest and spend the first phase of their lives caring for the brood. As they age, they move up and down the nest, performing more general tasks like food transport, seed storage and digging the chamber. They collect and transport the food brought into the nest and distribute it within the nest. Only the oldest workers leave the nest in search of food, with a remaining life expectancy of about three weeks. Within the nest, a constant upward movement of aging workers can be observed, with the older ones replacing those that die during foraging expeditions. Death occurs not primarily due to old age but because of environmental strains like heat, dehydration, or territorial conflicts.

Harvester ant nests are the largest and most intricate. They can reach depths of up to three meters and feature spiraling tunnels connecting pancake-like chambers. The chambers near the surface are densely packed and highly complex, while those at greater depths are simpler and more spaced out. Seed chambers can generally be found at intermediate depths between 40 and 100 cm. On average, a colony relocates once a year, usually in the summer. They do not move far; the new nest is typically about four meters from the old one. The new nest is similar in size and architecture to the old one, which raises the question as to why they move. Remarkably, excavating the new nest and transferring all the contents of the original nest (including seeds) to the new location takes only four to six days. Most of Tschinkel’s nest casts were made from recently abandoned nests, sparing the colonies from destruction.

These colonies have remarkable longevity, reaching maturity at around 4-5 years, with a life expectancy of over 30 years. The colony’s lifespan is closely tied to that of the queen, who serves as the mother of all ants throughout the colony’s existence. Mating only once at the beginning of her reproductive life, she stores a lifetime supply of sperm in a small sac called a spermatheca, obtained through mating with a dozen or more males. All females develop from fertilized eggs, while males come from unfertilized eggs (as is typical all for ants, wasps, and bees).

TRACHYMYRMEX SEPTENTRIONALIS

This is one of two fungus-growing ant species in the Sandhills habitat. Its range extends to Long Island, NY, and Illinois. The workers have spiky, bulbous bodies and move slowly but are extremely numerous, with up to 1,000 populations per hectare. Nests are easy to spot because excavated sand is piled up in a crescent shape on one side of the opening. If the pile is removed, the ants will redistribute the sand in the same direction. On sloping terrain, the crescent is typically downhill. When the ants encounter a prominent landmark near their nest, they align their sand pile with it. Hence, they navigate visually. The following question remains unanswered: the sand mound is reached by workers, who obviously coordinate the orientation. How this happens has not been investigated to date.

In nests around 150 cm deep, ants cultivate their fungus in egg-shaped chambers. They allow it to grow on a substrate of plant debris and caterpillar feces. The fungus is the sole food source for these ants and their larvae.

Around October, the ants disassemble and discard their fungus gardens. As the ground warms throughout the summer, the ants dig deeper chambers and relocate their gardens, filling the higher chambers with excavated soil. Despite their small size, these ants move approximately one ton of soil per hectare per year, thus playing an important role in soil mixing.

FORMICA DOLOSA

These ants are large, dig compact nests, and primarily feed on honeydew from aphids and scale insects. Their workers are fast and agile, and can be quite aggressive. Their light coloration suggests that they are mainly active at night. Workers possess large poison glands in their jaws and can spray formic acid, which smells like vinegar, to defend themselves. However, their nests, located just below the ground’s surface, are easy prey for armadillos and skunks. Some populations tend and guard aphids and scale insects, cultivating them for honeydew. These ants then feed the harvested honeydew to other workers called “tanker” ants, which shuttle between the aphid plant and the nest. In some populations, these ants guard the aphids around the clock.

PHEIDOLE MORRISI

This species forms large colonies with up to 80,000 workers. They build mounds above their underground nests, consisting of up to four shafts with small, closely spaced side chambers. In flatwood areas, the water table limits the nest’s depth. The ants and their brood are dependent on soil temperature and humidity. The population defends its boundaries against neighboring colonies.

CYPHOMYRMEX RIMOSUS

The ability to cultivate fungi as a food source has only been observed in American ants according to current knowledge. In the area Tschinkel studied, he found two species: Cyphomyrmex rimosus and Trachymyrmex septentrionalis. The former originally migrated from Argentina, where it is widespread. Fungus-growing ants feed on materials not utilized by other ants, particularly dead insects. They construct structures on which a yeast-like fungus grows, which they consume. The larvae are kept in chambers separated from the fungus gardens. Typically, the fungus grows in a filamentous form, but when ants cultivate it in gardens, it assumes a different, cell-like form.

Like most other fungus-growing ants, the workers carry multiple species of bacteria and fungi on their body surfaces, producing antibiotics to suppress the growth of parasitic fungi in their gardens.

The nest architecture of this ant species differs from its counterparts, appearing irregular, without true chambers, seemingly chaotic. The reasons behind this remain unclear, as most other ant species tend to build egg-shaped chambers to house their fungal gardens.

Mating flights occur in early summer. Males form a floating swarm with females flying in the center. Mature, winged females carry a piece of fungus from their birth nest on their mating flights. When establishing a new nest through digging, they create a structure using dead insect parts, on which they plant the fungal pieces and so start a new garden.

Walter R. Tschinkel (*1940, Lobositz, CZ) is a US-American biologist, myrmecologist, entomologist, and R.O. Lawton Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Florida State University in Tallahassee (US), where he taught for over 40 years. He is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated book The Fire Ants (Harvard University/Belknap Press 2006), the book Ant Architecture: The Wonder, Beauty, and Science of Underground Nests (Princeton University Press 2021), and more than 150 original research papers on the natural history, ecology, nest architecture, and organization of ant societies. In the early 2000s, he began researching the architecture of underground ant nests and pioneered the use of molten aluminum and zinc for making casts in the field. His casts have been displayed worldwide, including in museums in San Francisco, New Orleans, New York, Houston, Minneapolis, Washington, DC, the E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center in West Florida, San Diego (US), Birmingham, as well as in Paris (FR), Amsterdam (NL), Milan (IT), and Vancouver (CA). In his retirement, Walter continues his ant research on a smaller scale, sharing his insights through YouTube videos and short essays in a Substack newsletter.