Zoo Frankfurt

Exhibit developed by Dr. Johannes Köhler

Colony of atta leaf cutter ants

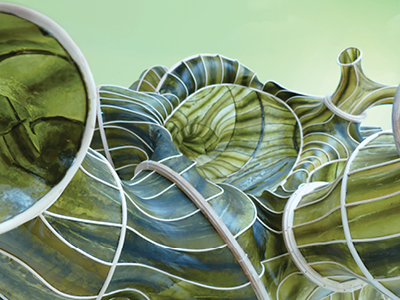

System of tubes and cubes with ants, food chambers, waste chambers

Various sizes

Courtesy Dr. Johannes Köhler, Zoo Frankfurt

Thanks to a collaboration with Frankfurt Zoo, the Frankfurter Kunstverein presents a colony of leafcutter ants that will inhabit the exhibition rooms for the duration of the exhibition. Guided by curator Dr. Johannes Köhler, Frankfurt Zoo has raised the ant colony up in glass enclosures. This allows visitors to observe up close the complex lives of these animals, which typically occur underground. Leafcutter ants are native to the tropical rainforests of Central and South America. They live in a complex yet highly efficient symbiosis with fungi. This reciprocal mode of existence enables both species to support or even make possible each other’s life functions. The symbiosis is so close that the two cannot exist without each other. Leafcutter ants are one of several ant genera that have developed this way of living.

Ants are an essential part of functioning ecosystems. They cultivate other insects (coexistence), feed on them (pest control) among other sources, spread plant seeds, dispose of dead organisms, and aerate soils with their complex burrows. They transport large amounts of nutrients to deeper soil layers, making them more fertile. Ants process substantial amounts of green plants, helping to maintain the nutrient cycle and promoting vegetation growth.

SYMBIOSIS

Working collectively, the large leafcutter worker ants use their mandibles to cut plants into smaller pieces and bring them into their nests. In specialized chambers, the ants cultivate so-called “fungus gardens”. The small worker ants in these chambers then chew the leaves into a pulpy mass, which serves as a substrate for the fungi. They carefully groom the surface of the fungal network, cleaning it of spores and fungal threads from other mold species. They repeatedly pluck small pieces from the fungal structure to feed to their nestmates. They also place new fungal threads on fresh plant material to cultivate more cultures. The ants also fertilize the fungus with waste products and their feces. The plant components, hard to digest, are collected by the ants and rooted, then decomposed by the fungal mycelium, converting them into a digestible substrate for the ants. Studies suggest that the ants carry bacteria on their bodies that not only inhibit the growth of harmful fungi but simultaneously fertilize the nutrient fungus as well.

In return, the fungus forms protein-rich nodules at its ends, providing the ants with proteins to feed their larvae. Additionally, the fungi break down the cellulose in plants, making it digestible for the ants. The fungus is able to break down toxins harmful to ants. The growth of the fungus depends directly on the food supply and the number of workers caring for it. The size of the ant community, in turn, is proportional to the size of the mycelium. The queen, through the number of larvae she lays, ensures that the population in the nest corresponds to the available food supply.

ARCHITECTURE OF ANTNESTS

Leafcutter ants build underground nests consisting of a complex network of tunnels and chambers. Nests can encompass up to 70 square meters underground and house several million ants. The various chambers serve specialized functions crucial to the population’s survival.

The fungus chambers are the central rooms of the nests. In waste chambers, ants dispose of plant remnants from the fungus chambers. The ant queen lays her eggs in the brood chambers, where the larvae and pupae are also nurtured. The brood is cared for by the worker ants. In addition to the fungi, the ants also store food reserves in special storage chambers. The reserves consist of fungi but also leaves, flowers, seeds, and animal remains. Each colony builds its nest individually. Changes in their environment and external conditions are responded to by adapting their nest architecture. The correlations at play here are not yet fully understood. The diversity of ant nests is demonstrated by the work of Walter R. Tschinkel.

THE DIVERSITY OF ANT POPULATIONS – SWARM INTELLIGENCE

Leafcutter ants, like all ant species, function as swarm intelligence. Each individual carries a limited amount of information. Coordinated interaction and communication give rise to efficient solutions for complex tasks through collective intelligence without a central authority. The ant population operates through a complex, emergent system of individuals possessing only local information. Ants have no knowledge of the overall state of the community but function through mechanisms based on social coordination. Ant trails, for example, form when individual ants leave a pheromone trail while searching for food. If an ant uses this path repeatedly, the trail becomes stronger.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Queens are the reproductive females in the population. They are significantly larger than other nestmates and are solely responsible for laying eggs. An ant colony typically has only one queen, with multiple queens being the exception. Queens are the only female ants capable of laying eggs. Also, queens and males are the only members of the population that can fly. This ability is important during the mating season and for founding new colonies.

The primary function of male ants is to fertilize the queens during the mating flight. Males are smaller than worker ants and usually have a short lifespan. After fulfilling their reproductive role, they die.

Worker ants are non-reproductive females. Workers can be divided into various castes and can vary in size within a population. Comprising the majority of the colony, they are responsible for gathering leaves, caring for the queen and brood, tending to the fungal cultures and defending the colony.