Eric van Hove

Mahjouba, 2016

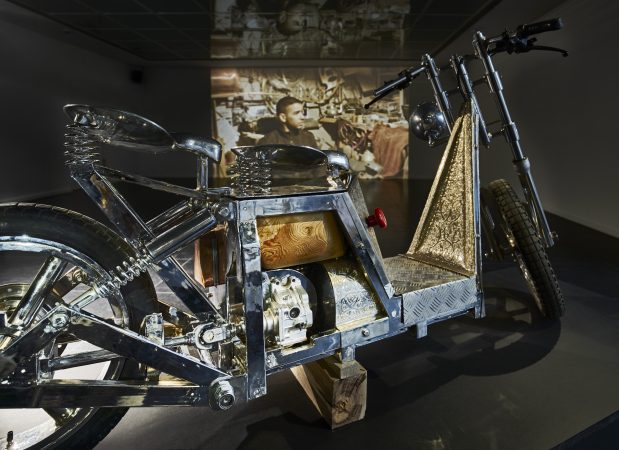

Mahjouba I, 2016

Mixed media, 15 materials including Middle Atlas white cedar wood, yellow and red copper, copper-plated forged steel, recycled aluminium, nickel silver, tin, cow bone, camel bone, rubber, cowskin, batteries, plastic, magnets, resin

200 x 70 x 113 cm, 119 kg

Courtesy the artist

Mahjouba derives from the Arab term Mahjoub, meaning “the veil covering the Holy.” Eric van Hove developed the simplified electric motor for this motorbike prototype in cooperation with the Institutes of Engineering and Communication at Dartmouth College, USA. By using an electric motor, the artist explicitly referred to Morocco’s national ambition to sustainably account for 42% of it’s power production with the world’s largest solar energy sysem, starting in 2020.

The first prototype was based on the Moroccan copy of a Chinese replica of a Mate T50 – a Japanese motorcycle from the 1970s. Eric van Hove deployed the strategy of appropriating and transforming industrial goods within the global production of commodities. With this piece, however, he transcended his own artistic practice by providing the sculpture with the aspect of functionality. Despite his reference to the art historical concept of the Ready-Made, Eric van Hove was recoding the sculpture as an object of utility. Hence the sculpture was meant to effect real social spaces without losing its legitimacy as art object.

The artist exercised the potential of Mahjouba I to evolve from its merely artistic aspirations into a project of local business and solidary economics. Van Hove added to the artwork the option it become a utility object, manufacturable in large numbers by local craftsmen, thus contributing to the relocation of labour.

Mahjouba II, 2016

Mixed media, 10 materials including chrome-plated steel, nickel silver, yellow copper, bolts, rubber, cowhide, plastic, electronics, 5KW Golden Motor electric engine, lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries

150 x 75 x 100 cm

Courtesy the artist

In the exhibition at the Frankfurter Kunstverein an unfinished prototype of van Hove’s second motorcycle project was further developed. For almost four months, Team van Hove cooperated with Frankfurt initiatives that had been invited by Franziska Nori as part of the studio project. The component parts of Mahjouba II mainly consisted of nickel silver and chrome-plated steel, to make the bike particularly sturdy. The powertrain technology combined part of a Caterpillar gear box with elements of the reverse gear unit of a Chinese cargo tricycle. Mahjouba II was powered by a 5KW Golden Motor and four lithium iron phosphate batteries. The production of the second prototype was based on 70% manual fabrication by the studio team and 30% pre-existing industrial components. The next generation of this motorcycle is set to contain component parts created by means of 3D-printing. Compared to the first prototype, the form of Mahjouba II had been simplified, the materials used were less specific and the design had been adjusted to local requirements. For example, several people should be able to sit on it at the same time, which is often the case on the streets of Morocco. In this art piece, van Hove recognised the potential for its use as a real vehicle, which could be produced and refined by everyone interested.

Mahjouba, 2016

Film

Creative Director Meriem Abid

Courtesy the artist

The film Mahjouba, which was produced specifically for the exhibition at Frankfurter Kunstverein, offered an understanding of the socio-political, economic and cultural context of the Mahjouba I prototype. The first part of the film gives an insight into the Atelier van Hove in Marrakesh. Here the focus lies on the collaborative working process as well as the craftsmen working with the artist on the project. As a fictional re-enactment, their life stories become an underlying narrative of the movie.

The second part documents Mahjouba’s cross-country road trip through Marocco. The journey from Marrakesh to the northern city of Tangier also navigates Morocco’s various linguistic and cultural landscapes. The encounters allow for people to share their thoughts on the future of craftsmanship and the potential of locally produced electric vehicles.