How to Make a Paradise – Seduction and Dependence in Generated Worlds

27.03.2020 — 16.08.2020

Opening: Thursday, 26 March 2020, 7 pm

Participating Artists: Tega Brain, Julian Oliver & Bengt Sjölén, Elisabeth Caravella, Kate Crawford & Vladan Joler, Fleuryfontaine, Keiken + George Jasper Stone, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, Lauren Lee McCarthy, Jaakko Pallasvuo, Julien Prévieux

Introduction by Franziska Nori

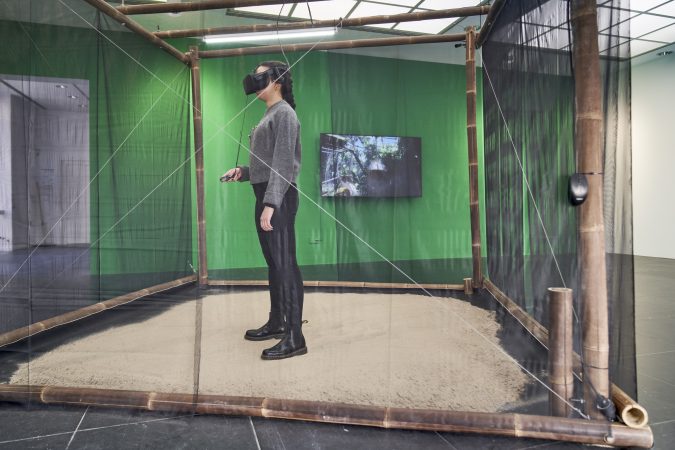

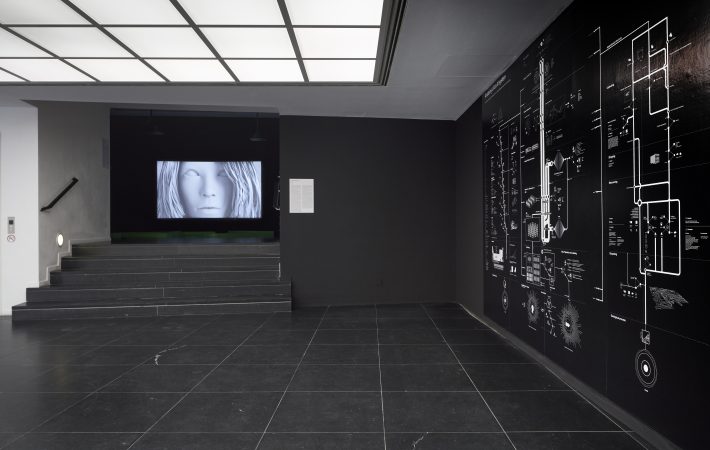

Under the exhibition title “How to Make a Paradise” Frankfurter Kunstverein has invited nine artists and collectives to present a broad spectrum of artistic projects dealing with the human desire for digital escapism, and the aspiration to expand human capabilities with technology. Curated by Mattis Kuhn with the support of Franziska Nori, the exhibition includes multimedia installations, digital films and VR-experiences.

Paradises evokes notions of fulfilment and longing. Longing for that which is far off, for beauty, for an effortless existence. Digital gadgets are accessible anytime, anywhere. They promise expansion of our comfort zone. They whisk us away from the here and now. They take us into worlds whose surface appearance is adaptable to our wishes. Playful, user-friendly and with a soft-toned voice, they help us effortlessly through everyday life.

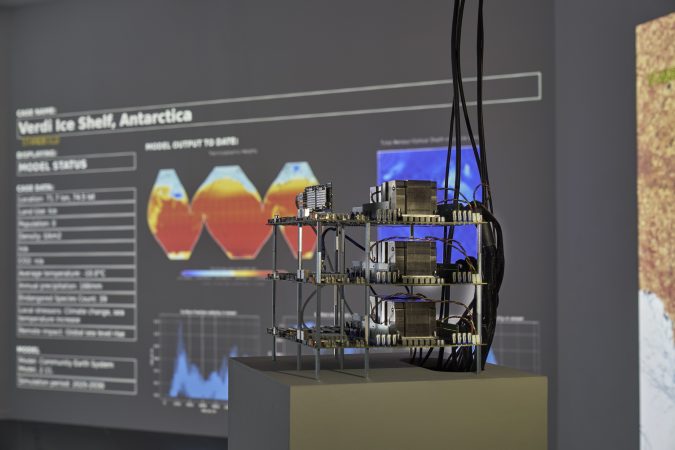

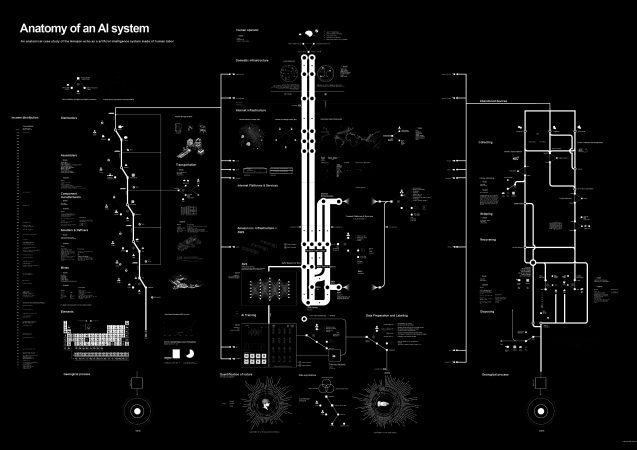

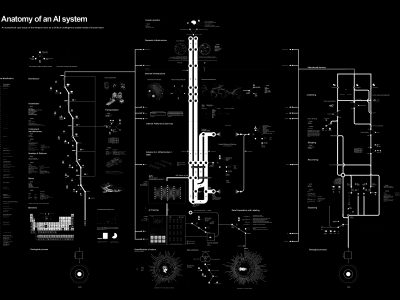

One focus of the exhibition is the use and effects of artificial intelligence. So that digital assistants can respond to a clap of the hands or a swipe of a finger, the globe is spanned by a powerful infrastructure of satellites, underground cables, databases and server farms operated by a handful of global corporations. These services use energy, raw materials and underpaid labor; but provide quick access that satisfies our immediate desires. Artificial intelligence, robotics and virtual reality promise an alternative, extended experience of the world without analog burdens. Solutions optimised by technology are seemingly free of human error.

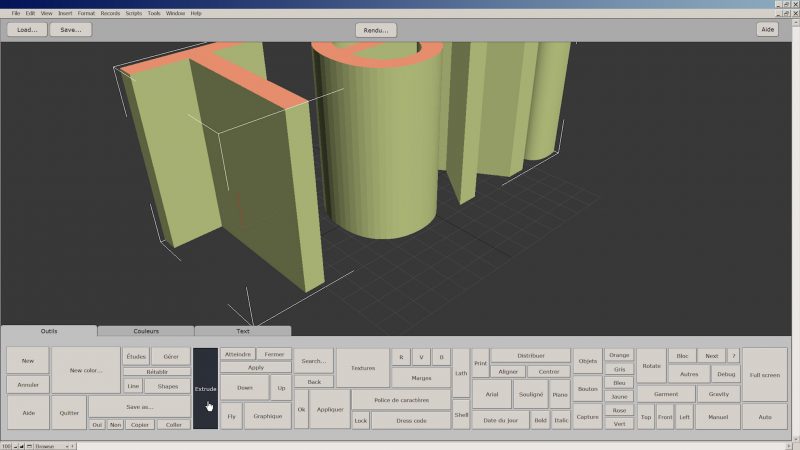

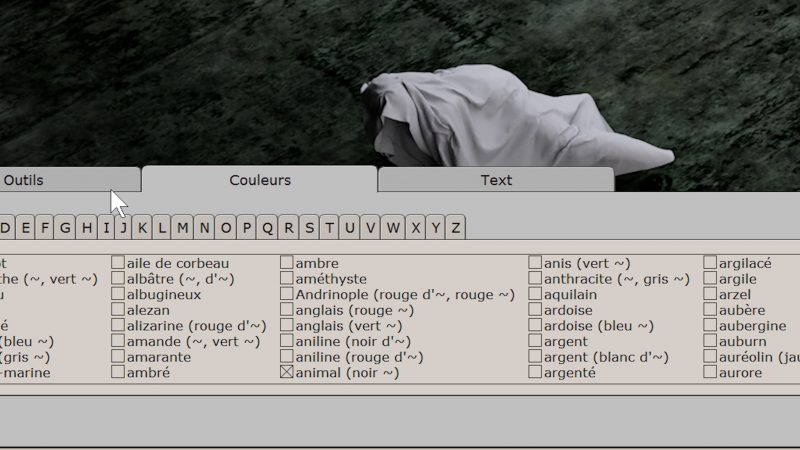

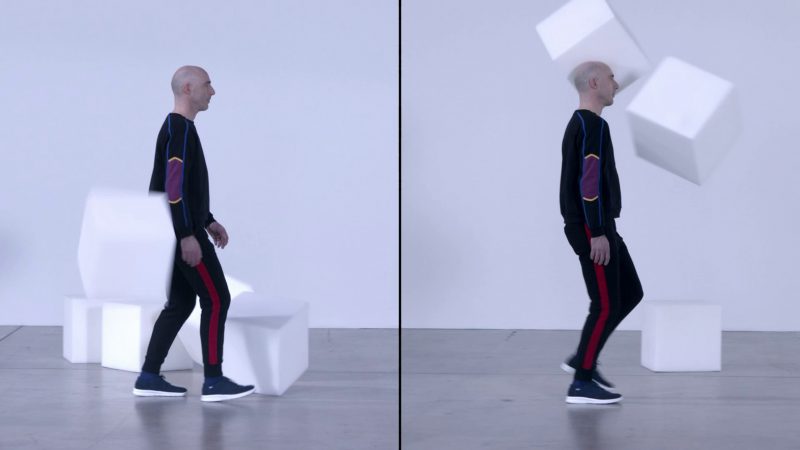

Lauren McCarthy; Kate Crawford & Vladan Joler; the collective Tega Brain; Julian Oliver & Bengt Sjölén; as well as Julien Prévieux, all problematize vastly different aspects surrounding A.I. in our society. Elisabeth Caravella and Jaakko Pallasvuo employ the recognisable aesthetic evident in online tutorials to explore the possibilities of artistic expression using technical materials.

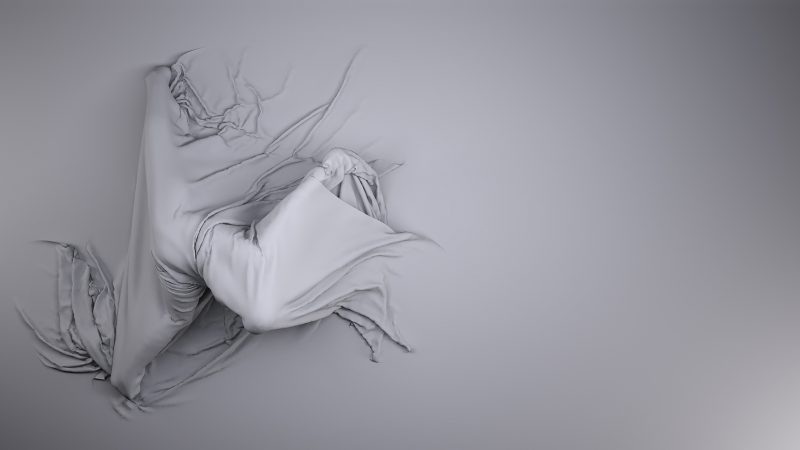

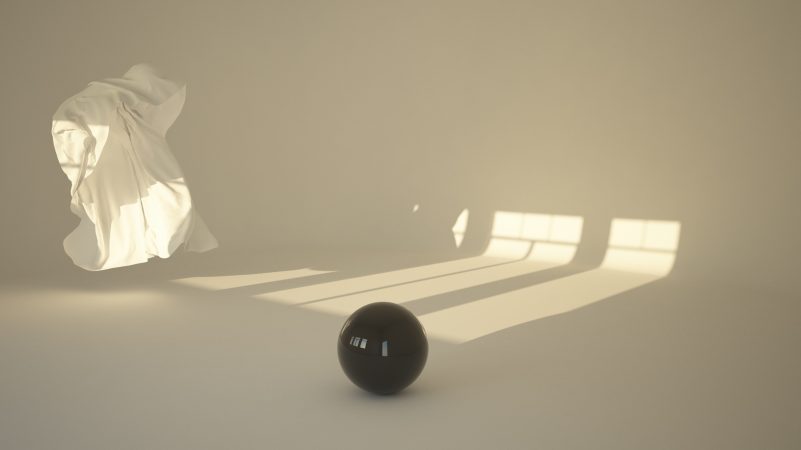

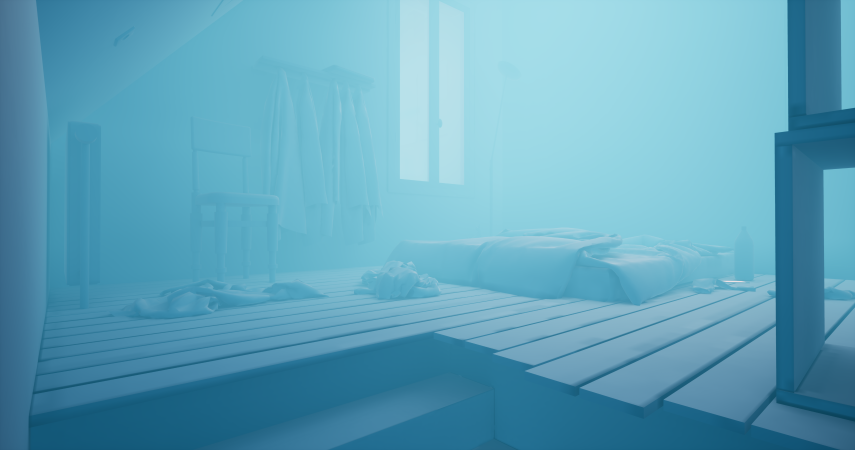

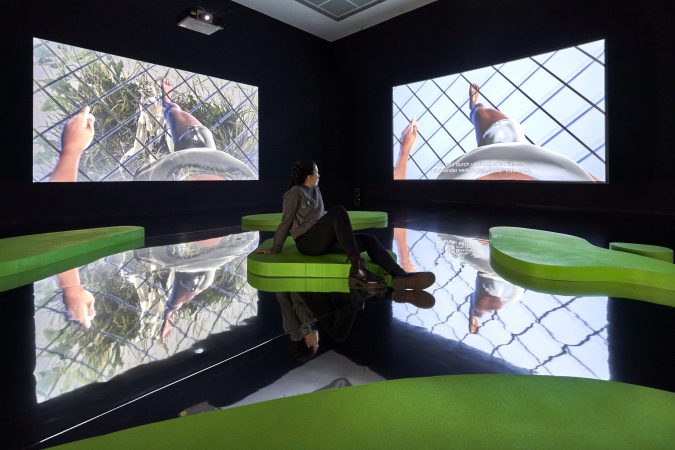

A second focus of the exhibition is individual experience in virtual worlds. Jakob Kudsk Steensen; artist duo Fleuryfontaine, consisting of Galdric Fleury and Antoine Fontaine; as well as the collective Keiken, all describe a feeling of loneliness in their work through varying stylistic perspectives.

The exhibition has selected nine positions that represent a relevant spectrum of current themes and forms of expression. The materials and methods used to create all the works presented include screen castings, programming code, software applications, Instagram filters and graphics programs. The image carriers are screens and smart glasses that provide access to extended artificial worlds in which visitors can temporarily lose themselves. Simultaneously they are also mirrors; two-dimensional surfaces that reflect an image of ourselves in the act of viewing for us to find.

“How to Make a Paradise” offers an individual area for each artistic work where the digital world is expanded and intensified within analog space. The nine works exemplify current artistic productions that succeed in anticipating emerging ruptures, both for the individual and on a political, collective level.

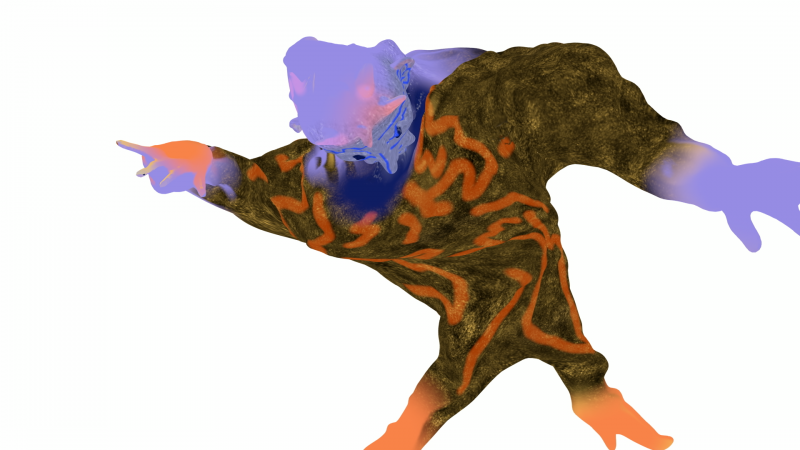

Retreat into digital paradises and controllable worlds is one pole, constant optimization of the physical is the other. However, the subliminal inherent themes in almost all of the works are isolation and doom scenarios. The desire for control through digital instruments and applications continually filters through. The longing for comfortable, iridescent worlds can be traced through the exhibition. The omnipresence of digital images asserting their own reality through flawless surface appearance reinforces the desire for individual self-optimization. We reflect ourselves in the digital plane. We continue to optimise our skills, our self and our individual world. In our individual paradise we yearn for seduction and the experience of closeness without intimacy, of excitement without consequence. With a digital body as an artificial manifestation of our staged self, we move through the matrix of the digital world in search of recognition and self-assurance through likes from online communities.

With the aesthetics of Instagram filters and motion graphics, a spectacle of animated images is created that stages the moment of attention in the fleetingness of the digital image economy. Increasingly, analog and digital spheres are merging into a meta-reality in which people act, meet and expect the realisation of what they long for.

Introduction by curator Mattis Kuhn

Through technologies like artificial intelligence, robotics, and virtual reality, we promise ourselves a better world. “How to” use-knowledge is usually greater than deeper understanding; the act of making normally exceeding the level of reflection on the goal. We are constantly optimizing our abilities, ourselves and our world, in the longing for an earthly paradise. This appears to be a double-edged sword – on the one hand is it a place of wish fulfilment, and of limitation and dependence on the other.

Paradise has been typically located in the afterlife, beyond the reality of earthly existence, in a virtual space. It is considered a desirable place; existence is timeless and there is no death. It is a garden or park. The environment is tamed and tailored to the needs of human inhabitants. Once, these gardens were designed by the divine. In recent centuries, humans have endeavoured to subordinate nature through technology. Gradually, paradise has shifted from a place beyond earth to this world. Humans are also equally striving to abolish the separation between themselves and the divine. The aim is to optimize existence in this world instead of waiting for admittance to an afterlife in the next.

Technological Oases

We can in fact make life on earth easier and more pleasurable. The development and practical application of algorithms, artificial intelligence, robotics and the Internet of Things expands the possibilities of what we can do with technology. Primarily, many things are becoming easier through the likes of smart phones, smart homes and personal digital assistants. Things are also improving substantially in areas such as medical care, resulting in increased life expectancy. As such, the quest for immortality does not only come to fruition in the afterlife. It can already start before death through the possibility of becoming a cyborg or freeing our being from our mortal body via mind uploading.

With the help of instructions, we can acquire new abilities and optimize ourselves and our environment. “How to” tutorials about digital technologies such as 3D programs, 3D printers, software for editing pictures and films etc., are exemplary of the growing prospects made possible by technology; even for private individuals. With these tools, not only are virtual worlds created, but we can actively change our physical world. Computer-based calculations shape our world(s). This gives the impression of subjective autonomy and potentiality at the hand of humankind.

Technological Enclosures

Just as the word paradise alludes to exclusivity in its linguistic stem (it means enclosure or fenced area), so too is access to technology exclusive and as such, it can limit us.

With the rapid development of technology, we are depriving ourselves of our livelihood by consuming or wasting natural resources in an unsustainable way – both for the production of all our technical devices and infrastructure, and their ongoing operation. The absolute subjugation of nature proves to be an illusion. In view of dwindling resources and climatic changes, we are striving to fabricate an exclusive extra-terrestrial paradise as an alternative, by colonizating Mars.

Demand for free digital services, attempts at self-optimization, or the desire for simply user-friendly convenience are leading to a continual increase in the aspects of our lives that are transformed into data, stored, and used for profiling. The constant bid for security requires the systematic surveillance of both physical and virtual spaces. Privacy is dissolving.

Increasingly, we are transferring our competencies to machines. Artificial intelligence is optimistically tipped at becoming a universal problem solver. In many parts of the world, it seems that the greatest amount of power no longer lies with states and governments, but with the private corporations that develop these technologies. By building and relying on their products, we make ourselves dependent on these companies. We become dependent on the tools are made available to us. Increasingly, technical devices are hermetically sealed in production so that they cannot be freely modified or repaired. Social media platforms limit the scope of action of their users, confining them to suit their own interest.

Make

The integration of an increasing amount of technology in our lives allows us to expand the scope of our possibility. We can do much more than we could a few years ago, but of course, our dependence on these technologies has also increased. In this way, spaces that were originally characterized by possibility, can become enclosures that limit the freedom we have achieved.

But will our skills as doers be in demand at all in the future, or will we just play the role of passive consumers? Can we even expect to be comfortably surrounded by paradise? Paradises, in their imagination and realization, always seem to be both oases and enclosures. At present, the realization is primarily driven by large technology corporations and their interests. Are there possibly still alternative interests, alternative goals? What might earthly paradisiacal visions look like? What could alternative narratives for a (paradisiacal) living world, which is neither ruthless towards the earth, exclusively made for a small part of the global population, nor bound for technocracy, be?

The exhibition “How to Make a Paradise” reflects these current developments. The exhibited works are critical, even potentially classifiable as dystopian. But in criticism there is always a call to action; within dystopia there is always utopia. It is important to find this, and to realize it. In this sense, “How to Make a Paradise” encourages visitors to individually reflect on their own optimization of self, instead of waiting for instructions to mechanically follow.