I am here to learn: On Machinic Interpretations of the World

15.02.2018 — 08.04.2018

Opening: Wednesday, February 14, 2018 at 7 pm

Participating Artists: Zach Blas & Jemima Wyman, Dries Depoorter, Heather Dewey-Hagborg & Chelsea E. Manning, Jake Elwes, Jerry Galle, Adam Harvey, Esther Hovers, Yunchul Kim, Gregor Kuschmirz, Noomi Ljungdell, Trevor Paglen, Fito Segrera, Oscar Sharp with Ross Goodwin & Benjamin, Shinseungback Kimyonghun, Patrick Tresset

Curator: Mattis Kuhn

Co-curator: Franziska Nori

The thematically organized group exhibition I am here to learn addresses adaptive algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI). The exhibition focuses on perception and interpretation as human qualities, which machines can acquire through learning procedures. The Frankfurter Kunstverein will present international artists, whose work thematizes the processes involved in machine perception and autonomous action.

Artificial intelligence is all around us. Other and foreign, we nevertheless share a common environment: at work, on the Internet, or in the connected, private home. The rapid development of computer technology, progress in the field of robotics, and a new generation of self-teaching systems are currently in a position to change numerous areas of life. Algorithms optimize online-dating and make transactions in financial systems, robots assume the roles of nurses, and adaptive learning systems navigate our cities’ infrastructures. The progressive expansion of the ability of machines to perceive, interpret, and autonomously act will cause a restructuring of fundamental sections of society: from maintaining privacy in coexistence with smartphones and interactive speech assistants, to automated systems used to assess other people and linked to insurance and credit systems, to fighting crime, all the way to a new judicial conception of responsibility and liability. The increasing use of robots and autonomous weapons systems in war has sparked a debate about ethical boundaries. Which human traits and behaviours do we want to assign machines, which are we able to, and where do we draw the line?

Intelligent systems are defined by their ability to not only passively register their surroundings, but also actively interpret them. But an interpretation is never objective. Does an artificial agent have the ability to engage in interpretation from its own point of view? Does an intelligent system have consciousness or a sense of self? Does a machine develop its own image of the world? And how much autonomy do we want to grant them now and in the future? The artistic stances on display at Frankfurter Kunstverein occasion consideration of these matters and present key components of the contemporary debate.

The exhibition I am here to learn: On Machinic Interpretations of the World investigates art’s role in a field influenced by specialist technicians, market interests, and increasingly privatized research, which, in turn, influence and alter numerous sections of our society. What does the phrase “I am” mean, if it comes from a machinic entity? What does “I am here” mean, if artificial intelligence has no body through which to position itself in the world?

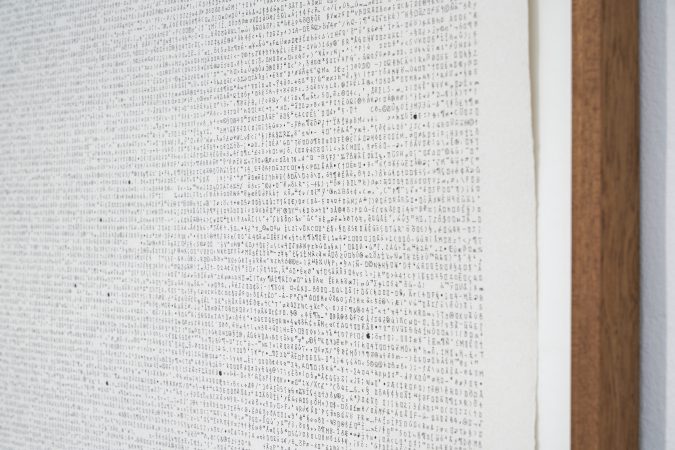

In his newest series of works, Trevor Paglen investigates the theme of so-called “invisible” images: invisible in the sense that they are exchanged as pure information – binary code – between machines so that the output format “image” occurs only when a human viewer is intended. In the exhibition at Frankfurter Kunstverein, Paglen presents works from the series Adversarially Evolved Hallucination. It deals with images that emerged from the interaction of two combined systems of artificial intelligence. The first system is an image recognition algorithm. The artist fed it images from the fields of literature, philosophy, and dream analysis so that it would recognize patterns within them. The second system is an image-generating AI that creates forms without external stimuli, but which, in the context of machine learning, is called “hallucination”. The two systems exchange the images, optimizing the image-generating software until the image-recognition algorithm can identify subjects in the images. The results are dark, surreal forms that show shadowy figures.

The video installation Behold these Glorious Times! illustrates how machines learn by being fed countless subjects with similar content but different appearances to train their ability to recognize patterns. By increasing the speed, flood of images, and tempo of the electronic sound, the viewer is drawn into a flickering whirlpool of pixels.

Artist and bio-hacker Heather Dewey-Hagborg developed the piece Probably Chelsea in collaboration with American whistle-blower Chelsea E. Manning. Manning was imprisoned from 2010 until 2017 for disclosing 40,000 classified documents about the Iraq War to WikiLeaks. At the time, Manning was undergoing hormone therapy to transition from a male to a female identity. Throughout her years in jail, not a single image of her reached the public. Manning sent a cheek swab and hair sample to Dewey-Hagborg in 2015 from military prison. The artist analysed the DNA and, thanks to a DNA-phenotyping process and a 3D printer, developed and produced thirty different facial models – thirty machine-designs of Manning’s possible physiognomy – which are on display in the exhibition.

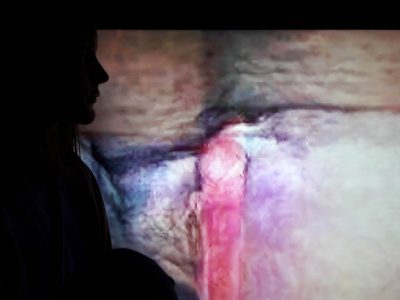

Jemima Wyman and Zach Blas present a four-channel video installation entitled I am here to learn so :)))))). In it they evoke the chat bot Tay – the Microsoft learning system that caused a sensation in 2016. Tay’s developer hoped that the artificial intelligence would learn to speak like a nineteen-year-old American girl. In order to accomplish this, the bot trained its speech and intelligence by conversing with countless users online. In its conversations, though, the system quickly learned misogynistic, homophobic, and racist expressions, which it naturally repeated. As a result, the chatbot eventually had to be shut down. In Blas and Wyman’s piece, Tay is brought back to life and speaks with us, reflecting on her existence as an AI and presenting her digitally assembled body, which was constructed by converting her profile image into a three-dimensional form. Tay moves through ‘hallucinated’ image landscapes generated using Google’s DeepDream software (this free software was also used to generate the exhibition’s key visual). She ponders her ability to recognize patterns, the use of explicitly feminine connotations in chat bots, and the new life of an AI after death.

Sunspring is a film by Oscar Sharp, Ross Goodwin & Benjamin, whose script was the first to ever be written entirely by artificial intelligence. Ross Goodwin developed the AI-software, which was fed countless science-fiction scripts and later named itself Benjamin. Over the course of different steps of discovery, Benjamin independently generated a script from the information it received. The director and three actors took the artificially generated piece as a template for the film, which they understand to be about a love triangle. The algorithmically developed dialogue and stage directions are partly sensible and precise, but also partly illogical and absurd. Sunspring, like other works in the exhibition, traces the problematic that arise from the interaction between humans and artificial intelligence. At present, it is still possible to recognize the machinic aspect of the algorithm as such. But with rapid advances in technology, it may become increasingly difficult to distinguish machinic from human behaviour.